Significant Otters features monthly interviews with some of my favourite writers who happen to have books dropping and who (more importantly) also happen to be Otters. Significant Otters, if you will. The name was suggested by this guy on Twitter I don’t know. June 2022’s guest is two years younger than me—if that fact alone blows your mind, wait till you read the rest of this interview.

I Zoomed with Jessica Kim on the first Sunday of June from her home in Los Angeles. We chatted about her first chapbook, L(EYE)GHT, which Animal Heart Press published back in April, as well as being visually impaired, among other things. I’m in awe of everything she’s doing for young writers, for the greater literary world, and for visually impaired writers like myself.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity, this time because Jessica kept bringing up things I was planning to get to but that we hadn’t gotten to yet. Goddamnit, Jess!

🦦 —O— 🦦

Ottavia Paluch: So you’re in LA right now.

Jessica Kim: Yeah. I think before I talk about the fact that I’m in LA, I want to say that I [haven’t] been in LA for longer than I am now. Which is 3 years. I was born in Texas but then I moved to the Bay Area and then I moved to Korea and then Singapore and then I finally came to LA. That’s kinda crazy, because 3 years seems like a long time but 2 years of that was the pandemic, so I’ve been in my house the whole time. And honestly, I don’t really know what LA is. There’s this perception that LA’s sort of like this big city where everything’s going on, but for me personally I feel like nothing’s going on? So I can’t really tell you much about the city life. But I did go to Rupi Kaur’s world tour thing that happened here yesterday and that was the first poetry thing that I had ever seen here, which is kinda crazy. But that was interesting.

Can I ask, do you spot a lot of celebrities regularly?

I’d like to say yes, but no.

Have you ever been recognized on the street?

No.

Damn! You’d think that being on NPR, on All Things Considered, people would know who you are.

Maybe, but then, do people read the news anymore?

I don’t know, man, at least not our generation!

Though my English teacher did say that she heard me on the radio and I didn’t tell her about the NPR thing, so—

Oh, that’s SICK. What was that conversation like?

She was like, “Oh my god! I was driving in the morning and it was, like, a gloomy Wednesday, and I heard your voice on the radio.” And I was like, “Oh my god!” And she made this whole metaphor about seeing the sun, like, peak through the clouds and stuff. It was great. Quite crazy.

You have the best teachers.

Literally.

So we’re here to talk about your chapbook, but first I want to discuss how you got here. Because I think the path you took to get to this point is really interesting and unique.

I actually started writing in March 2020. It feels like a long time ago but if you look at it objectively it’s only been a little more than two years. And I guess with us all quarantining, all being locked in our own rooms, it kind of forced me to look inwards and examine my emotions and that kind of thing. I wasn’t a poetry person or generally a literature kind of person before the pandemic, but that really fuelled me to try something new…I would write multiple poems, or at least one a day, which kind of helped me grow from a kind of really bad poet to a slightly decent one.

I was fortunate to find a bunch of mentors that I really admired from afar, just reading their work and sometimes meeting them over Zoom. I think one person who really got me inspired to write, especially about disability and about these kinds of vulnerable identities, was Sandra Beasley, and I actually was in a Zoom workshop thing with her and it was kinda cool. I was like, “Should I write about disability when no one does it?” And she was like, “Yeah, you should!” And she even introduced me to a blind writer, so that was pretty cool.

Can I ask who that was?

It was actually Constance Merritt, and one of my poems in the book has an after-note for her.

Yeah, yeah, we’re gonna get to that! So you were, like, in direct contact with her?

I participated in a three or four-day workshop with her and afterwards I emailed her a paragraph, or more like an essay-length kind of email, where I was just talking about things, and among [those things] was talking about disability, and that’s kind of how the conversation started.

So in terms of, like—you have all these cool mentors and stuff, and you’re writing all these poems and you’re going from shit-tier to god-tier in, like, a month…

*laughs*

At what point in your writerly journey does the book emerge?

The first time I was proud of a piece I had written was maybe in August of 2020, so around five months in. And I started thinking of writing a book maybe in October or November. So that’s pretty soon. A little too soon in retrospect.

I was texting you the other day when you sent over this book to me and I said something along the lines of, “I was expecting this book to be 10 pages, not 45.” There’s so much covered in these 46 pages. 22 poems in total, if I’m not mistaken. Do you have a favourite?

That’s a good question. The “Poem About My Disability” series is what grounds my chapbook. I honestly don’t know if they’re my favourite pieces but they’re definitely important ones.

That’s such a good [segue] into my next question, you don’t understand! You couldn’t script it better.

This is clearly scripted.

Oh yeah. You’re reading off a teleprompter.

I am!

I love that trio of poems. Because I think they bookend things, in a way, and I want to go through them one at a time. The first poem in the book is called “Poem in Which I Do Not Talk About My Disability”. And it’s one of my favourites because of this stanza:

“I cannot differentiate sky from // skyscrapers, museums from churches. A refractive error. Everything requires / sight: cinemas, nightclubs, even sight- / seeing. I avoid confrontation with my eyes.”

That is so good!

Thank you! I feel like that line arose from me being non-observant. I can’t see things like streetlights, signs, or whatever’s going on in the city. So that’s where that line arose from. And I think this poem in general is kind of encapsulated in the phrase “I avoid confrontation with my eyes”. It’s me trying to avoid talking about my disability, which is kind of ironic as you delve into the book.

I actually wrote this poem last, which is kinda crazy. I guess it’s me wanting to introduce the book, and also not introduce it in a way? Like, if you look at the trajectory of the book, it’s kind of like a journey of recognizing and loving and appreciating my visual impairment.

It’s funny that you mention the last bit, because later on in the book we get to “Poem in Which I Talk About My Disability” which we talked about at the start. That’s the one with the Constance Merritt epigraph. This was the first poem of yours that I had ever read. Tell me a little bit about how this one came about.

This was actually the first poem I had ever written about disability. Sometimes I’m really proud of it and sometimes I’m like, “Why did I write that? What was I saying when I wrote that?” I think after Sandra Beasley introduced me to Constance Merritt, I started reading her work, meaning the 3 poems [of hers] that are available in POETRY Magazine and Poets.org. The italicized lines are really me trying to be in conversation with the pieces that she wrote that I’ve read. The part about being an apprentice ghost is a reference to her poem about ghosts and being unable to see things. It kind of arose out of fear, being scared to talk about [my disability]. And I think in some ways it’s pretty muted. I don’t necessarily talk about my own experiences but just generally the idea of being unable to see, and I thought that maybe it could be more of a universal piece to people.

This is kind of where the chapbook started, and when I wrote it I didn’t know that I was going to turn it into a chapbook, but it was kind of like, yeah, I know this is one of the pieces that I really want to expand on.

The last poem in the book is called “Poem in Which My Disability Talks About Me”. I love it when poems sort of…how do I say this…take your expectations and invert them from the get-go.

Me too.

Do you know “Schehezerade” [sic] by Richard Siken?

Um… mayyyyybe?

You’re a teen writer. You HAVE to know. It’s the “these, our bodies, possessed by light” poem.

…Oh.

See, of course you know it, who doesn’t?!

I said “maybe” because I didn’t know it was pronounced that way. Of course I know it.

I don’t know how to pronounce it myself! I’m just making fun of the fact that I don’t know how!

I don’t know either! It’s okay.

But to me this [“Poem in Which My Disability Talks About Me”] is the “Schehehehezerade” [sic] of the book. Which is a weird comparison to make because in Crush, that’s the first poem of the book. And meanwhile your poem ends the book. But I think they’re both really, really beautiful poems that sort of wrap things up in a nice bow for the reader. They’re like…mission statements for their respective books. And the last line in this poem, and therefore the book, is “Look, / I should’ve gazed into those eyes, / everyone’s eyes, the glamour of them all.” I love that so much. I think it’s so wholesome.

I love that line too. I really wanted to subvert expectations, because at this point I had all my poems assembled and I was kind of like, “Oh my god, this is so depressing” and that wasn’t my intention, right? Writing this chapbook has made me a lot more confident in representing my disability and this poem tries to reflect that. That last line that you mentioned kind of goes off my inability and also unwillingness to make eye contact, but it’s also me trying to be unapologetic in looking at people and just appreciating people because of the fact that I can still see, like, something, I guess? I wanted to uplift myself and also the communities that feel so suppressed because of their inability to see. It’s kind of a motivating, wholesome poem, as you mentioned. I [felt] a lot of self-affirmation writing it.

When you talk about determination and self-affirmation—I’m just thinking now, like, when you write about gazing into people’s eyes, is it kind of like a dare to people? Like, are you telling people, you know, “hey, look at me, I’m Jessica friggin’ Kim”? Is it a “This is who I am” kinda statement?

Not necessarily. I feel like I’ll never do that in any of my poems. I’m more like, “Please don’t look at me!” But I think when people make eye contact, I usually look down or look away and it’s…something default and instinctive for me to look away from people. Maybe because I’m ashamed of my abnormal eyes and how they shake all over the place and how I don’t really look straight at people. But I guess “I should’ve gazed into those eyes, / everyone’s eyes” shows that…it’s not really me wanting people to look at me but me wanting to look at other people.

Thank you for clearing that up, because I was thinking, “You know what, I’m probably wrong, but I’m still going to ask her.”

You know this already; one of the reasons I really wanted to talk to you about this book is because we share something in common in that we’re both visually impaired and we both identify as disabled. You write a lot about that in this book, and you do so in a way that I really have not seen before from other writers, other poets, other young writers. And so when I found out about you and I started texting you, I was really blown away, because I wasn’t really aware of anyone else who wrote about being visually impaired. Especially kids my age.

I’m blind in my right eye and I don’t have a lot of vision in my left. Sight and vision and light are things that I love to talk about in my work. And you sort of dared me to write about those things in a way that I was afraid of doing in the past. Can you give our readers a brief overview of your experience as someone who’s visually impaired?

I was technically born blind, but that’s because the lenses in my eyes were blocked and then I had to get those removed because…one should probably get them removed, maybe? I’m not a doctor. I wear contact lenses now but without them I can’t see anything. I can see, like, the biggest letter on the eye chart and that’s basically it.

Growing up, especially before I was a writer and before I was a high school student, I really hated being visually impaired. As a child, I felt so different from everyone else, and then people were like, “Why are your eyes like this?” And I think a lot of them meant it out of curiosity but for me it was like, “Oh my god, I’m different, and I hate this.” And that impacted me really negatively. I was really scared and traumatized by having a visual impairment and also just being different from other people in the sense that I had to go to all these medical appointments and then I had to wear contact lenses, which I first started wearing when I was four years old. It was intimidating.

But I think me being visually impaired has been such a crucial part [of who I am]. I felt it was so imperative to write about visual impairment. Now that I’ve had a chance to express my struggles but also my experiences, I’ve become a lot more confident and it’s something that I tell everyone, whether it be putting that I’m disabled in my third-person bio, or asking for accommodations every time I need them. It’s given me a lot of empowerment and inspiration to just be myself.

I’ve gotten a lot of power through poetry but especially poetry centered on visual impairment. I think it’s really inspiring that people who are disabled look up to me, in a sense. And it’s kinda crazy because, like, for example, I really looked up to you, before we started talking. It was real.

Every time you say stuff like that to me, I’m just like, “Oh my god.”

It’s the same for me, too.

It’s funny, the two of us look up to each other, but we write about our visual impairments in really different ways from each other. Our styles aren’t really the same, but I think the message that you can take away from both my stuff and yours is similar. Was writing about your condition something that came naturally to you or did you force yourself to start talking about it?

It was natural. I always thought there are certain topics in the teen writing world that are sort of, I hate to say it, but mandated in today’s society for people to generally write about. For example, being an immigrant. That’s really common in poetry, and in a lot of my poetry as well. Compared to that, my visual impairment was an identity that I felt needed to be represented, but wasn’t. I guess not a lot of people share this disability, and a lot of people aren’t really comfortable with saying that they’re disabled, or including that [fact] in their poetry. But for me, as much as I wanted to talk about other things, like being an immigrant and being Korean-American, I also really wanted to talk about my visual impairment. I was scared to do it, but I never thought, like, “Oh my god, I need to sell this identity.” That kind of thing.

Yeah, this is going to buy me so much Starbucks!

While we’re on the topic, “Braillet” to me is such a gorgeous and heartbreaking poem. It’s this quick, short little prose poem thing. And you write about how “your fingers pirouette across / braille books, the bumps an aching / for possibility. What could have been.”

It’s like, MAN, you know? It hits me so hard because I’ve always been scared of learning braille. To me it’s like if I…learning it would be like accepting something I’m not ready to accept yet. Which is blindness.

I’ve also never formally learnt it, but I can tell you what all the letters are and stuff. I think it’s scary, because when I go to the eye doctor, sometimes they tell me, “You’re going to be blind sometime in the future.” It’s a possibility. That kind of scares me because it would take away all the things that I took for granted in my life. “Braillet” was, in part, an imagination of that, but also a present reality for me. Every night, after I take off my contact lenses, I need to walk to the fridge in the kitchen to get my eye drops, which I’m supposed to put in every night, so—

SAME. SAAAAAAAAME. Twice a day! Alright, continue.

I’m glad that I’m not alone!

But usually it’s 2am, 3am, and none of the lights are on, so that’s where this poem started from. Everything’s scary to walk across, knowing that you’re probably going to bump into something. “Braillet” is kind of a re-imagination of that, ‘cause I think one thing that’s really different is that the speaker in the poem is not uncertain about walking in the dark. There’s a lot of dancing imagery. That’s something I aspire to do. Even learning Braille, although it’s scary, is also inspiring in the sense that you’re kind of learning a new language and a new way to communicate. Just like [how] the invention of Braille itself is really inspiring. And I’m kind of afraid to shift into that sphere of communication. But maybe when the time comes, it’s not something I should be so fearful of.

Do you think as a visually impaired poet you see the world differently than other poets?

In some ways, maybe? Yes? I think different as in seeing things more stupidly than others. I take, like, five minutes to learn how to work…a coffee machine or something, when other people can do it in three seconds.

You ever tried opening a lock?

Yeah, I did. Doesn’t work! This is why I can’t use the lockers at my school.

ME TOO! Me too.

Virtual high-five!

Yeah, so I think in that way I do see things differently than other people. I can’t really name certain things but I think subconsciously, or even unconsciously, I have a different perspective from other poets, but in other ways I feel like some experiences of mine are pretty universal. Even the idea of not being able to see things; it’s not only restricted to visual impairment, especially because the idea of seeing things can be taken in a more abstract and metaphorical way. My inability to see certain things, but also my ability to see things in a new perspective, is a communal experience, and I hope others can take that into consideration when they’re reading my chapbook.

How does it feel to be an actual, like, published author, with a real-life book and everything? I can’t imagine what that must be like. Especially at such a young age.

It feels…like so many different things. At school, it feels kind of weird. I don’t like when people come up to me and be like, “Oh my god, you published a book!” And I’m like, “Oh yeah, I did!” I don’t think embarrassed is the right word, because I’m not embarrassed with the fact that I write and that I have a freaking book published, right? But I think it’s something that feels really disjointed from the rest of my identity. In real life, I’m an introverted person, I’m the quiet kid. Having a book and having people talk about my book out of the blue—people I barely know—is very humbling. Also a little terrifying.

In the Twitterverse and literary world, I feel like being young and publishing a book is really gratifying. I’ve met a lot of people who have admired my work or blurbed my work or mentored me or just said nice things about my work. Every time I get those kinds of messages, it feels kind of unreal. I don’t know if half the people on Twitter are real, but it feels good.

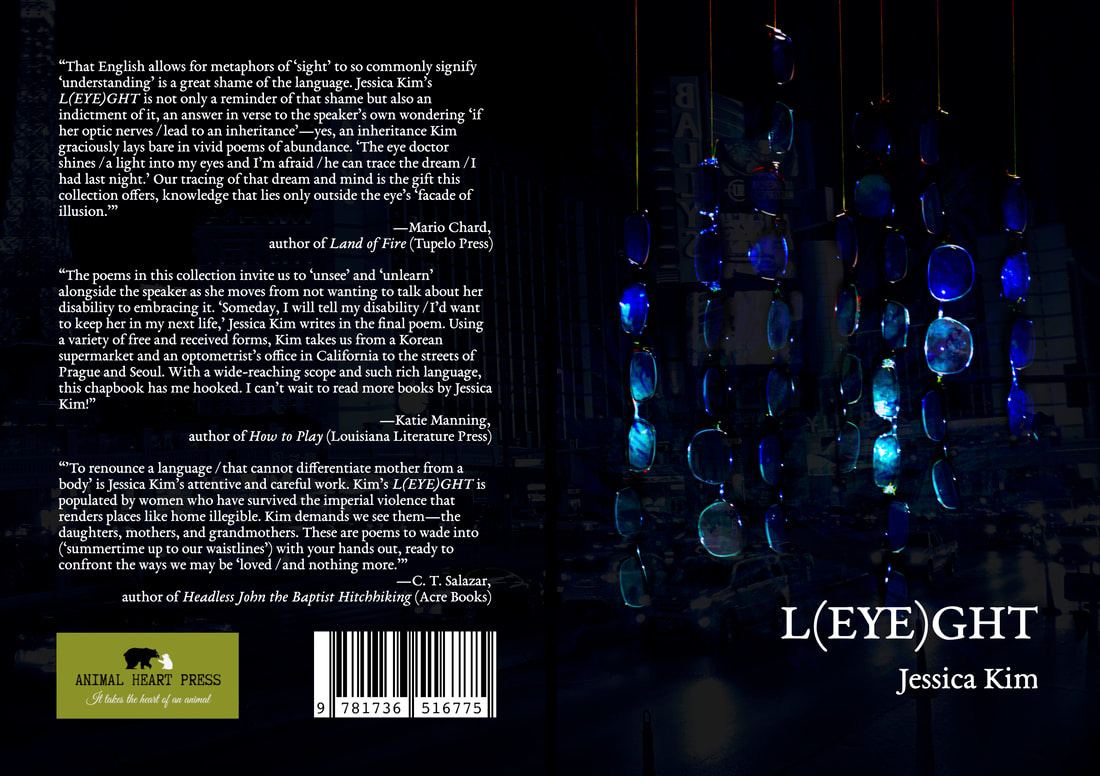

Our friend Miye Sugino did the cover for this book, and it is just stunning.

I could gush about Miye for this entire meeting. I was really uncertain about what I wanted for the cover and I kind of left it up to Miye and asked if she could come up with the art because she has the brainpower for that. She gave me a few ideas, and I liked the glasses idea the best. If you look at it closely, you can see pictures of my childhood in some of the glasses. There’s one of me riding a horse for the first (and last) time.

We can’t talk about this book without talking about the title. I always pronounce it in my head as “lee-aught”. I know that’s not how you say it, but that’s how my brain works. And I love it because it’s a pun. I think more books should have titles that are puns.

I agree!

Was that always the title of the book, or did you have a bunch of working titles that were along the lines of, “I Can’t See, Goddamnit!” by Jessica Kim?

At first I wanted to call it TW(EYE)LIGHT, but my publisher, the team at Animal Heart Press, who are honestly the most amazing people ever, thought it was an allusion to the Twilight series. Ha.

There’s a really nice section in the acknowledgements that I want to mention:

To the brush I grabbed during doljabi—a Korean tradition that foretells a baby’s future—on my first birthday. The brush symbolizes a writer, and as an avid believer in fate, I think this was all meant to be.

That is FASCINATING. That is, like, the best origin story ever.

I think so too, honestly. It was one of those traditional Korean brush things that you write Korean characters with. My parents thought I wasn’t going to be a writer because they thought I was bad at writing, and I don’t really blame them because I was really incoherent. Oftentimes I didn’t really think of myself as a writer. I usually thought I was a STEM person. [But that anecdote] is me wanting to acknowledge myself, in a way. To others it’s an inspiring story but to me it’s like, “Oh yeah, I know that maybe I can be a writer, and maybe I should be one.”

You just ended your term as Youth Poet Laureate for the city of Los Angeles. And recently you were named a finalist for the NATIONAL Youth Poet Laureate program, where you got to go to D.C. and perform at the bloody Kennedy Center. I want to know more about this trip because it sounded like a blast.

It was. That was my first in-person poetry experience—meeting writers, performing, being in a space meant for writers. I thought that was the coolest thing ever. I got to meet people [that I’ve only seen on Zoom] with legs! It’s kinda crazy!

I was scared to do the Kennedy Center performance, but the people there made me feel so at home that ultimately I felt like I expressed the best version of my poem and of myself. We went to this place called Busboys and Poets, a bookstore and performance space, which really inspired me to look for those kinds of spaces in L.A where poetry is a communal thing. Especially the spoken word scene.

My term as L.A. Youth Poet Laureate is ending and that’s really bittersweet for me. I remember the application asked for a resumé and I didn’t have one so I bullet-pointed a bunch of things. I didn’t know what I was doing. I still don’t really know what I’m doing, but I have more confidence, I have a vision for my work. I’m really happy about that.

You also run a dope litmag called the Lumiere Review. Which is actually how I found out about you in the first place. It’s been crazy watching it grow from this…thing…to a dream journal for so many people and a fanbase of, like, 10,000 people, and with all these big-time names in its pages and judging its contests. I can only imagine how challenging it must be for you to basically be in charge of all of that.

I do put in a lot of time and I enjoy every aspect of it. Yesterday at midnight I started formatting pieces for the June issue and the last one I did was your piece.

I forgot about that!

Lumiere’s usually something I do past midnight. We get a lot of submissions that I don’t want to say no to. We just opened for subs on June 1st and then on June 1st we got like 60 submissions. It’s been a dream of mine to publish other people’s stories. I knew I wanted to be an editor before I knew that I wanted to be a published poet. The time I put into curating it and growing it and retweeting things has been full of joy.

What’s next for you, writing-wise, life-wise, whatever-wise?

I get asked that a lot these days. It makes me think about what I want to do in the future, whether that be tomorrow or in a few years. Because a lot of my big projects are wrapping up, and my school year just wrapped up, my summer’s pretty open and I’m super grateful for that, since I get to rest a little. I want to try writing some creative non-fiction. Writing more, I think, is what my future looks like. Just for myself instead of trying to meet a deadline, and that’s kind of liberating for me.

Maybe this summer you should start a Substack page!

I would need to commit to it every week. That sounds crazy.

Jessica Kim is a hibernating polar bear, the runner-up for the United States National Youth Poet Laureate position, and a YoungArts Finalist in Writing (Poetry). Some pretty cool magazines like POETRY Magazine, The Adroit Journal, and Frontier Poetry have accepted her poems. Jessica invented her author signature while taking the AP Computer Science A multiple choice exam. She thinks you should reach out to her on Twitter @jessiicable or Instagram @jessicakimwrites for a signed copy of L(EYE)GHT.

Buy Jessica’s book through:

Learn more about Animal Heart Press, the publisher of L(EYE)GHT:

Follow me on Twitter:

And, finally, if you enjoyed this interview with Jessica, tell all your friends about it!

Stay significant, Otters! I’ll be back on Monday.