OOOOOOTTERS! This is Ottavia Paluch from Things You Otter Know. Welcome to the very first edition of Significant Otters!! My first guest is a wonderful friend of mine who is a year younger than me but you wouldn’t be able to tell because she’s literally the second coming of Einstein.

I spoke to Nova Wang via Zoom on Earth Day from her home in southeastern Pennsylvania. We chatted about her new book out now with River Glass Books and the people that helped turn that book into a reality. Her words are going to change the world, both in a figurative and literal sense (as we’ll be getting to later on in this interview.) What a joy it was to pick her brain for an hour and a half.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. In part because Nova would just NOT SHUT UP.

🦦 —O— 🦦

Ottavia Paluch: So of course we’re here to talk about your new chapbook with River Glass Books, but before I get to that I figure we should start with how you got here. Like, give me the lowdown on when you started writing.

Nova Wang: I think when I was really little, I just read, like, a shit-ton of books. That was just all I did with my free time, because I had an attention span in the past. And then in third grade my best friend Linda and I decided we wanted to try to write, like, a fantasy novel or whatever. So we did that during recesses and stuff. We would tell it to each other and then I would transcribe it later. We did that for a couple of years and never finished. But that was the thing that started it all, and then my middle school had this program called “Writing Seminar”. Shoutout to Dr. Settle, who was the teacher who ran that. And that [course] introduced me to flash fiction and short fiction, which are the forms that, or, the prose forms that I primarily write in now.

And I did not really hardcore dedicate myself to writing until I would say the tail end of sophomore year, because that was when COVID was starting. And I found an online teen writing community on the Discord server. With you!

With me!

And so many of our other friends. And then the momentum and the passion from all these amazing people sort of propelled me forward, so I don't know if I would be writing as much or as well as I do right now if it wasn't for finding that community.

But like like in terms of, like, this book, when did that start? [Because] at this point you've been running for a gazillion years. At what point in the timeline does the chapbook kinda emerge?

Some of the stories were written before the concept, before I thought of writing a chapbook. I had previously written “Games” in about March of 2021. And then I wrote “Changeling”. I had written those 2 stories independently but I noticed how hunger and family relationships and desire and cruelty were common to both pieces. So I wrote, like, a little thing of bullet points to myself in my personal Discord server where I talk to myself because I’m a nerd. And I marinated on it for a while, and then I talked about it to some friends. Like Emma.

Oh yeah!

Yeah! I talked to them about it first, and I threw out the idea of writing a chapbook with this key motif, I guess, or this common thread, and then as I wrote more stories, I also began to discover more thematic threads as well. Instead of this, like sort of superficial thread of the metaphor of hunger. I had, like, a long list of ideas, but I ended up whittling them down to the 5 stories, and then fleshing them out.

Do you have a favourite one?

I'm going to say “Changeling” was my favourite in many ways because it came so easily. I like to say that I have a maximum of one piece a month that just comes super easily, and this one was mine for April.

So it’s been a year.

Yeah. Last April. Goddamn.

We should have a “Changeling” One-Year Anniversary Party.

Oh, for sure.

So the process for that story was I was looking at artwork by Ren Hang which I had first seen on Twitter, and then I was looking into contemporary Chinese photography. Then I went on Pinterest. I made, like, a giant Pintrest board of, like, stuff with similar vibes. And then I made a playlist of music with similar vibes. It was all, like, Mitski and Phoebe Bridgers and Half Waif.

But I made those 2 things, and then I started thinking of lines, or, like…the voice of the narrator, just sort of like coming into my head. So I started writing down that stuff and it sort of coalesced into a story very quickly. That was one of my fastest short stories - maybe the fastest short story draft I have ever written. The voice came very naturally to me, and I think I wrote the entire first draft in 2 sittings, which is extremely fast for me. It usually takes me, like, forever.

I'm very fond of the voice. I like how morbid it is. I can't confirm whether it's the most technically strong piece in there or not. But I like it. I like the imagery. I like the narrator. It has a soft spot in my heart.

I mean, I love all these stories, but I think what I like about that one specifically is that while all of the ideas in this book are so original, that one especially makes me think, “Shit. She did not come to play.” You know?

I do want to go back a little bit because I want to talk about the start. I think books in general, like, if they don't hook you within the first 2 pages, you're done. Right? You're gonna toss that thing out the window.

And so I think what your book does is not do that, right?

Thank you! *laughter* I try.

The first one was originally in trampset, and it’s called “Games”. Which, I mean. Such a creative title. So descriptive. But this story, to me, is about a game of suffering. Wherein the person who suffers the most wins. And the opening scene, if you will, talks about stab-scotch. Which for those if you who don’t know, is that stupid, STUPID, dumb game where idiots stab a knife between their fingers and try not to make themselves bleed profusely. But the girls in this game talk about how they would “dance [our] knives faster and faster before metal met flesh and blood and blood watered the weeds, sky splintering on our necks.” Like, good God, Nova. What an opening. What a visceral way to open a story, to open a book.

Yeah, that’s a good question because I did not have a set order in mind when I was writing these stories. I ordered them later. And the thing about this piece was it sort of introduced the themes of, like, machoism a little bit. And desire, because she's supposed to have a burning desire to win, right?

[She’s] sort of taking us from this very typical mundane setting. I think this story has the most “realistic” setting in the book. It’s a bridge into the more surrealist or fabulist happenings in the rest of the pieces. Bringing in the themes of, like, hunger and desire and cruelty and sibling relationships. Just helping the readers transition from our world into the world of the chapbook.

I do want to talk about “On Building A Nest,” which opens with the narrator talking about her mother, specifically her mother’s very badly-built house. And this daughter says that the reason her house is so messed up is because her mom has this philosophy which reads as follows:

You cannot determine something’s worth before it is finished, and most everything finished is bad—corrupted by greed or rust or the general corruptness of its maker.

Is that a philosophy you yourself believe in? And maybe this is a stupid question, but is the first part something that you apply during your writing process?

First of all, I would like to say that I do not think that everything finished is bad. But the idea that you cannot determine something's worth before it's finished…I haven't actually thought about this very carefully but I think it is something I believe in. And when it comes to the writing process, I think writing is like a journey where, as you go, you learn more things about what you're trying to say and about yourself, and it's like excavating these ideas that sometimes you didn’t even know you wanted to express. So I think that process is very nonlinear.

There are many moments in the middle of a piece, or especially in the first draft, where you’re like, “Oh, my God, this is hot shit,” you know. In the derogatory way. Like, “This sucks!” And in revision you're actively looking for things that need to change. But I do believe that you can't definitively say, like, “This is awful!” until you have discovered what you were trying to discover through the piece. And there is an argument that nothing is ever truly done, right, because in theory you could keep revising or keep changing it ad infinitum.

I want to spend a little bit of time on “Meals at the End of the World”, which is the only unpublished story in the book. First of all, sick title. Very apocalyptic. It’s written in this…what are those poems in fancy forms called?

There are many fancy forms, I’m afraid.

The word in my head is “contraptual” [sic] but that’s the one that goes forwards and backwards.

Oh, contrapuntal. That’s the one that you can read in 3 ways, and there's like 2 columns.

Okay, that’s not what I meant. Screw it, we’re calling it a NUMERICAL L I S T.

My burning question is, were there initially more than 10 things in this list? Because I can imagine there were probably dozens.

The answer is no, surprisingly. Yeah, I think I was writing these and I wanted to get it to, like, a nice number. And the reason I didn’t list a million different things and then whittle them down slowly is that I was trying to make it so every subsequent item carries a word from the previous item into it, preferably in a new way. I don’t remember if it’s completely correct, because I read it once and thought, “I DID THIS WRONG!!!!” But that was what I was trying to do. So I had no room in between to have, like, random things. It was always 10.

You know what’s crazy? The thing you mentioned about one number bleeding into each other in the list - I did NOOOOOT notice that. It completely flew over my head. That’s craft, you know?

I think it was super obvious to me because I was doing it but nobody ever brought it up. The idea was that every item in the list would inherit part of the previous item in a slightly different way. Like a mutation.

Would inHERIT. Ahahahahahahaha!

Good one!

We can’t talk about this book without quickly talking about the title. It’s SUCH a good title. And there’s this whole thread of hunger unravelling through these stories. When you were putting this book together, did you have that kind of thread in mind or did it just happen naturally?

I knew the title before I finished the chapbook. I don’t know at what exact point but it was very early on. I just knew I wanted it to be about families and the things we inherit. Like hurt and cruelty and the desire that connects these characters, I guess? I knew from the beginning that hunger would be the literalization of these things, in the bodies of these characters. So the title sort of came from those 2 ideas, because I think inheritance and hunger are sort of the core pillars of the project. It just made sense.

There’s a page in this book that I think more people should be talking about. Two, actually. The first is the cover. Our friend Taylor Yingshi did it. It friggin rules.

It’s beautiful. I gasped the first time I saw it.

The other page, though, is the acknowledgements! Our friends Ai Li Feng, Amy Wang, Emma Chan, and Kaya Dierks were first to see these stories. I don’t wanna embarrass them or anything, but how did collaboration play a role in the making of this book?

The first person I told about this chapbook was Emma. I sent her a screenshot of the Discord rant I sent to myself and we began brainstorming ideas. She saw this through from the very beginning and she helped me think of my initial web of ideas surrounding hunger. She read the first drafts and probably the second drafts of many of these stories and helped me polish them, both on a structural and line level. She was really with me for every page of this book. As was Amy Wang, who…well, the three of us have a group chat that she’s a part of with Emma. I would send them screenshots and we would talk about it there. So the two of them were my first readers. They were really important to the development of the chapbook.

Ai Li is one of those readers who’s very important to me because she thinks about writing, especially fiction, in a very careful, intentional, and intelligent way. And she can pull apart the pieces of what you’re trying to think about and understand the core of what you’re trying to say and bring it to the forefront and make it the best that it can be. She is at the heart of many structural revisions that I’ve done because she helps me isolate what is working and what there needs to be more of.

Kaya is one of my ideal readers because she always gets exactly what I’m trying to say. Sometimes people read something and they’re like, “oh, I think you were trying to do XYZ” and I’m like, *in a high-pitched voice* “no, not really, but you know, that works too!” But Kaya always gets it. She puts it in a way that is way smarter than I could ever think of. And she helps me really find my path to the story.

You also mention your teachers in the acknowledgements. How big of a role did they play? Because teachers never truly get the credit they deserve.

Well, Dr. Settle I mentioned earlier. Mrs. Ebarvia was my AP Language and Composition teacher last year. She bought my book! She was so amazing because we were completely virtual my junior year when she was teaching me, but she would always try to make the classroom a safe space, especially for queer students of colour, etc. She was one of the few Asian-American teachers at my school. I became really close with her. My friends and I would talk with her outside of class. She introduced me to the idea of thinking critically about the Western craft traditions that I have grown up with and that I have taken for granted, and sort of decolonizing my approach to writing. Seeking out other craft traditions. Or wondering why the Western style of writing is considered “good writing” and who is it “good to”. And what the power structures in play [are]. She also introduced me to the book Craft in the Real World, which is an amazing book that I think all writers should read. Even straight white men!

Mrs. Wilson and Mrs. Smith are the advisors of our school’s literary magazine, which is one of the main creative spaces in my school. They’ve been with me since ninth grade and they’ve always been the most encouraging people. They’ve always created this encouraging and healthy environment where we can get excited to share our work, to learn from each other, to be inspired by each other. Big shoutout to them for, like, being interested in the creative work I do outside of school. They both bought copies of my chapbook, which are now in their classroom!

Did you charge them money for your book?

Hahahaha. I was going to give them free copies but they all insisted on paying me.

Speaking of money! How does it feel to be an actual, like, published author?

It feels really good! This is something I was dreaming about since elementary school. And even though this isn’t, like, a full book, it’s like -

You have a Goodreads page, so you’re, like, a certified author.

It’s, like, you know - it’s bound, it’s physical, this is a BOOK in many definitions of the word. And getting paid for my writing was such an amazing feeling. Not to be all capitalist or whatever, but it felt good to be able to do something and make some coin out of it. And for people to like it enough to give me coin for it. Which is nice, because, you know, sometimes you just need some coin.

For this book, actually, the only money I’m making post-publication is by selling signed author copies. However, I have no qualms about this, because the proceeds are going towards grassroots environmental conservation and infrastructure and education projects in the Amazon Basin. And my publisher was really transparent with me about this process and what exactly they were doing [to get that to happen]. They are fundraising through the Artists for Climate Justice Fund and proceeds from their books. So that is something that is really important to me and that I’m really glad I can help with in any small way.

I didn’t know that was happening and I’m so glad it is. That’s sick as hell.

When they emailed you saying they were going to publish your book, what did it feel like?

That was so exciting. I was so worried that no one would want my chapbook! I had only sent it out to 3 presses at the time and they were the first press that responded. It was like a matter of days. To have that sort of excitement and energy about the project from their end as well was so tangible throughout the entire editing and assembling and promotional process. The moment of acceptance where I realized that somebody actually wanted to platform my work was really important to me. And so validating.

That whole process you’ve mentioned - when those ARCs show up at your door, what’s going through your head?

That was so incredible because it was just a giant box that said RIVER GLASS BOOKS on the front. And I’m like, “Oh my god.” So I open it and there are these two stacks of books tied with twine. And it’s my book. And I’m like, “Oh my god.” It’s a real thing, a physical thing that I own…and that other people are owning…and that people are reading. It was the actualization of this dream that I had had. Because even though I knew that it was happening, it finally felt real to me.

"In this collection, Nova Wang brings us visions of hunger with an artist's eye for detail. Every story is vivid, shining, full of power. While the reader is pulled into the characters' hunger and desire, we are left sated by the gift of these cutting, beautiful stories."

Cathy friggin Ulrich wrote that. About YOU! And she’s right, by the way. What’s it like to be a big deal?

I would not define myself as a big deal! There are many bigger deals out there. HOWEVER. Cathy is somebody who has supported me for a while. She first published one of my earliest pieces of micro-fiction, “Space-Time” in her magazine Milk Candy Review. Her acceptance email was so sweet and she’s consistently supported me since then. It just felt very satisfying [when she blurbed my chapbook]. She’s a writer whose work I really love.

Tommy Dean also blurbed this. Which, I mean. What a guy.

What a guy!

And our lovely friend Kaya as well, who we mentioned earlier. She’s your friend too, but I think I get the upper hand on this one because she’s subscribed to my Substack. I tend to forget how young she is. 19? 20? And you’re 18. Do you think you’ll top this project when you’re 30?

I hope I don’t peak at 17. Because I wrote and had this accepted at 17. This was a really great culmination of stuff I’ve been ruminating on and writing about for the past year, but that I’ve been thinking about for much longer. I think this was a really great first big project for me.

I am working on two other novel-projects that I hope will be finished sometday. Crossing my fingers for publication in the future. Hopefully by 30 I’ll have something bigger than this!

Were there any stories or books that influenced this book?

In general the writing of K-Ming Chang and Ocean Vuong have really influenced my prose style, or the way that I approach writing in general. I think this is somewhat evident in my writing style in that I’m sort of a…shitty Xerox of that. But the way that they bring poetry into their prose was something that influenced me a lot. [K-Ming] engages with viscera and with imagery in really amazing ways. But her stories…they…

They’re very good.

They’re very good! Let’s go with that. I love them a lot. In, let’s say, May of last year, I just read and reread everything she had written that I could find. I’m very obsessed with her. It might be kind of obvious.

Something people might not know about you is that you also write really, really sick poems. What I wanna know - and this is a very cliché question - is whether your poetry informs your prose in some way. Because to me there’s this powerful kind of precision that I think only poets can have. When you think of someone like Ocean Vuong, his prose is so…tight, right?

EXACTLY! He’s insane.

Have you read his new one?

Time is a Mother? Parts of it—I have not finished. But I’m going to re-enter my literacy era.

I re-entered my literacy era with your book.

Thank you! I’m honoured.

I mean, my foundations are in prose because I wrote prose for many years. I started writing poetry in…October of 2020. Even before that, though, I was always drawn to lyric and to imagery and I think that’s sort of what help me branch into poetry and into that kind of writing. My poems definitely inform my fiction. The tight imagery and the metaphorical connections that are very characteristic of poetry but are not necessarily as prevalent in prose, I suppose. However, one thing that’s interesting to me - and that I think one of the editors at CRAFT pointed out in their editor’s note when they published my story “Graftings” - but which is definitely core to my writing process is the associative process in poetry. This idea of parataxis where you move from line to line and there’s not necessarily a super concrete logical connection between the lines. But they are associated in a way that creates meaning. The flow between lines makes sense and creates meaning in that negative space of, like…the missing connective tissue that tends to be in prose but isn’t always in poetry. So basically that associative idea is really key to my prose as well. Because I will sort of cling to an image and circle it.

I love the idea of, like, excavating every bit of this image in your head.

Yes, exactly! Just keep beating the dead horse. Beat it ‘till it’s beyond dead. And then take out the gross bits and…there’s your…thing.

That is something that’s really key to my process in both prose and poetry. On the structural level, it’s sort of apparent in my prose if you look at “Graftings,” how I keep talking about fruit and parenthood. And then on a line level, the imagery and metaphors I use really inform how I will construct the rest of the piece. Because especially in the beginning of a story, I am discovering the image system that I want to use in the rest of it. The line level for me also informs the piece on a structural level. And I really discovered this when I started working on my novel because it’s such a big project. I started to realize how small choices that I made with imagery would change the way - would affect the way I wrote the subsequent scenes and the ripple effects that this had. Basically what I’m saying is the associative or image-based mindset or approach that I learned from poetry changed the way that I write prose.

That was a really long answer. I went in circles there.

You were going in, like, triangles and squares. You were all over the place.

While we’re on it, did any of the stories in this book start off as poems?

I think this depends on how you categorize poems and flash fiction. To me, this is a collection of prose and these pieces began as prose. However, people have told me that the first and last pieces in this collection could be poems. The last one, “Meals For the End of the World,” is especially open to interpretation because it’s just a list of things! To me the individual things within each item are prose, but are they? It could very well be some sort of list poem, though.

I’ve got a couple of questions left. Do you have any advice for people who are putting chapbooks together, or those who want to in the future?

I don’t think this is prescriptive advice, and I only have one chapbook experience, so I’m definitely not an authority on this. I’ll just say what I did, which was - well, pretty early on in the process, I came up with the themes, [along with] atmosphere and metaphors that I wanted to carry through the chapbook and that I knew would stay consistent and that would make it feel extra cohesive as a project. Just to make everything fit together in a really nice way. However, I know that some people do not do thematically-linked chapbooks so, you know, if that’s not your vibe you don’t have to do it. But that is what I did.

And in writing each subsequent story, after I figured out what I wanted to do with the chapbook, I threw a really broad net with the…scant through-threads that I had. Which was only one, and it was hunger. But I started writing more stories and began to realize the core of this chapbook. I began to do that very consciously with the rest of the pieces in both their conceptualization and their execution. Which was slightly hard because, to me, coming to the page with a super clear idea of theme is hard to execute. The process of writing, to me, is like a process of discovery. I treated it less as a clear concrete thing that I had to adhere to and more as a guide that could help me form the pieces. As long as I was keeping the through-lines in the back of my head, the pieces could naturally fit around them. And there was still that process of discovery, and realizing what facet of my themes I was addressing with each individual piece.

And then in putting them together I actually put together several different assemblies of [the book] and I showed them to people and asked, “which one do you think is best?” Some of the friends that I mentioned before talked to me about which ones they liked best and why. And why they thought the thematic flow [of a certain assembly] worked. The progression in the sort of apocalyptic atmosphere that grows throughout the chapbook as well as the progression of the characters, and introducing new ideas of, like, motherhood and daughterhood. That was a very experimental process. I just tried a bunch of different things and settled on one.

My penultimate question. Why do you write?

Such a good question! This is something I’ve been thinking about because it’s something I started doing because I wanted to tell stories and that was something that felt natural. But now, I think there’s something in addition to just the pure joy of discovery that happens in writing, and, you know, the satisfaction of it, and the way it has changed the way I view and interact with the world around me.

I’ve been thinking a lot about archives. And writing, of course, is a process of archive, in a way. Even creative writing. I want to interact in a dynamic and creative way with the existing archive of my people - Chinese people and queer people - in both a respectful and conscious way. Because the process of writing is also kind of like a process of memory and of remembering.

Let me re-say this so you don’t have to struggle to decipher what I’m saying.

Let me help you. When you started writing, what compelled you to do it?

When I first started writing, it was the draw of the story and of being able to tell stories. And as I continued writing, I fell in love with the way that it shapes the way I see the world, and what I notice, and the wonder it kind of instills in simple things. I was reading this interview with Mary Ruefle where she was talking about joy and she was talking about this poem she wrote about peeling an orange. And somebody was like, “WTF is this poem? What’s so special about peeling an orange?” And Ruefle was like, “Well, what is more special than peeling an orange?” So there’s that sense of wonder and perpetual discovery in interacting with the world.

And now I’m also thinking more critically about writing as a queer and as a Chinese person and the gaps that are in the “canon” for people like me. As well as the history and the culture that has shaped people like me, and how I can interact dynamically and creatively with that.

Nova, thank you so much for doing this. That was so much fun.

It was! Thank you for asking such good questions.

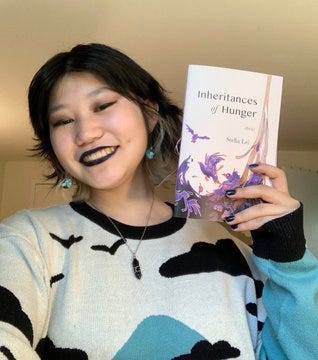

Nova Wang is a teen writer from Pennsylvania whose work appears in CRAFT, Four Way Review, Peach Mag, and elsewhere. Her debut prose chapbook, Inheritances of Hunger, is out now with River Glass Books. She is an Editor in Chief for The Augment Review, she has two cats, and she tweets @novawangwrites. She will be attending Harvard University this fall.

You can buy Nova’s book through:

Follow me on Twitter:

And, finally, if you enjoyed this interview with Nova, tell all your friends about it!

See you on Monday, eggheads.

THIS IS THE SWEETEST INTERVIEW!! STELLA & OTTAVIA YOU BOTH R SO COOL <3

Excellent work! It’s great to learn how the magic happened. Congrats!