Significant Otters: MJ Gomez

Discussing Love Letters from a Burning Planet while on an actual burning planet!

Significant Otters is a monthly interview series exclusive to Things You Otter Know.

(We haven’t done this in a long time, so I figured you were in need of a refresher.)

SO features casual conversations with writers about their new books—writers who (most importantly) happen to be Otters. Significant Otters, if you will.

My last Significant Otter was Tejashree Murugan.

A full archive of SOs can be found here.

BECOME A SIGNIFICANT OTTER: This will likely be my last interview of the year unless someone you know has a cool book out next month. But I’m also ready to start scheduling interviews for 2024!! In either case, reach out via my website or my Twitter (I refuse to call it X).

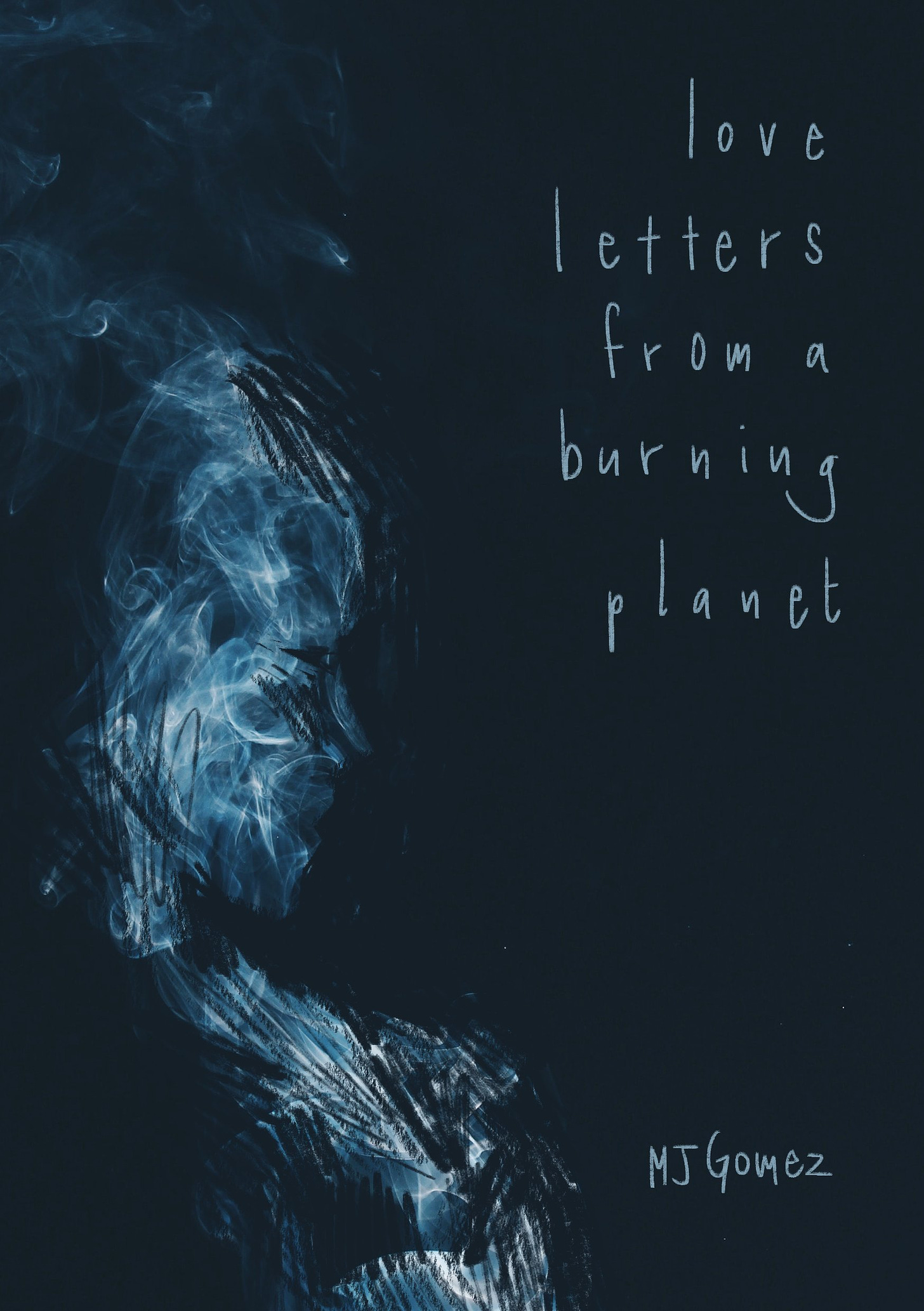

November 2023’s Significant Otter is MJ Gomez (he/him), whose chapbook Love Letters from a Burning Planet has just been published by Variant Literature.

I got to chat with MJ over Zoom around the start of autumn about his book and also about ghazals and identity and fried chicken. It was so wonderful. I honestly have no idea how MJ and I initially got in contact with each other but I’m so glad we did since he is a really fantastic poet. His work is like a cross between all your fave contemporary poets—Vuong, Siken, the works. He is also very charming and kind in face-to-face conversation, as is to be expected of all Otters.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity because MJ said “just” too many times.

🦦 —O— 🦦

OTTAVIA PALUCH: So do people ever ask about Michael Jordan and stuff when they find out your name is MJ?

MJ GOMEZ: No — when I was younger it was Michael Jackson and Michael Jordan. Now the kids ask me if I’m Spider-Man’s girlfriend.

[ridiculous laughter] You’re kidding!

And I don’t even have red hair!

I’m nervous now for all the hard questions you’re about to ask me.

I mean, nothing hard yet because I have to ask you first of all where you’re calling me from.

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. I was born here. This city is sort of a melting pot. There's a lot of immigrants here. And we have the best fried chicken in the world! No, seriously. It's called Al Baik and it's like Jeddah’s pride. It's so good. I don’t know how to describe it other than the fact that KFC sucks here and they know it.

Would you say that being from Saudi Arabia has influenced your writing in any way? Or are you writing from more of an internal place?

I think so, definitely. Not necessarily living in Jeddah or like being from this certain city but rather, growing up Muslim, still being a practicing Muslim but having this entire spiritual journey that I've been going on since, I don't know, for my entire life. And I think the chapbook touches upon faith and religion a lot. But I actually wrote this — I started putting it together in November 2022.

Oh my god, how are you getting to my questions before I’ve asked them?!

I think I’m just following the script! [laughter]

I don't think Jeddah has necessarily influenced me directly. I don't really write about urban city life or anything. But there's a lot of turmoil in the book and a lot of references to Islam. The second poem in the book starts with a quote from the Quran and the Quran itself does influence a lot of my recent work. I don't really think it has influenced this chapbook in particular, but it's just always been there. A lot of this chap really comes from the subconscious, actually. So it's a little bit hard for me to pin down direct influences. Again, though, definitely growing up Muslim has influenced me a lot.

I think of what Sarah Ghazal Ali said in an interview, that she doesn't think she would have been a writer if she wasn't Muslim. I do think that a lot of my approach to poetry is rooted in…belief in the divine. And a lot of my work almost pushes up against that perceived absolute truth.

You’re, like, so smart.

You say that in every interview!

Is it my fault that I get to talk with the coolest friggin young people on the goddamn planet?!

[laughter]

I swear I'm not just saying that because I say it to everybody else. [laughter]

You mentioned the subconscious earlier. Are you saying that the most badass lines in this chapbook just kind of…came out, or are you referring to something else?

I think in general all of my big lines come from the subconscious. I think that's just being a writer, you know? Like, it’s 2AM, you're about to sleep, but oh, wait, the stars have aligned and now you got to take out your Notes app. [Ordering] them was definitely quite intuitive. I did the “floor thing".

Oh yeah.

I love how we both know what the floor thing is.

I actually didn't print out all of my poems. I did the most horrific, super digital version of it, where I took screenshots of my poems. And then I put them in Microsoft Paint, and I just moved them around a little bit. [laughter]

To go back to the writing process, a lot of these poems were definitely written…I don't want to say intuitively, but I think that's just my general approach to writing. One of them came from me wanting to write a poem because I hadn't written one in a while. That one was “Study of Daylight”. I sat down and told myself, I am going to write a poem, and I just didn't get up…

A lot of my work comes from putting my own voice into conversation with other poets. You may notice there's a bunch of after poems in here. Ocean Vuong, a poem in response to one of Bhanu Kapil’s 12 questions in The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers. One after Everywhere at the End of Time by The Caretaker, which is this one huge, six hour noise music album about dementia. And also, a lot of personal things happened in my life in late 2022. And I just felt the need to put something together. I definitely do feel that there was a force that guided me, pushed me to create Love Letters.

Has it always been present in your life, this force? Or only recently, when you started putting this book together?

I always say poetry is my survival mechanism. And I definitely think that I put this together as a survival mechanism. Two years ago, when I started getting really serious about poetry, I noticed that when I was at my lowest I would write poems.

You started writing poems two years ago?

Um, okay, this is so embarrassing, but I started writing poems when I was a freshman in high school. They weren't good. I graduated high school and I wanted to be an English major, but my poems were so bad. I just didn't read. I had like one poetry book and it wasn't even that good. It was like Instagram poetry, whatever. I hadn’t put in that time to get to know poetry or to delve into poems in general. But I guess part of me knew I'd always write. I just hadn't put in the work until I was a freshman in college.

So what was the moment where everything changed?

I had really fallen in love with Richard Siken’s Crush. As all the young poets do. I know I'm not special. But yeah, I started writing those kinds of poems. Which basically just meant a lot of violence. And a lot of bullets. And then I found Ocean Vuong, so even more violence! [laughter]

And this is a detail only I would notice, but I have a really weird reverence for the word bullet because of how strong of an image it is. That word only occurs once in Love Letters. And it's at the very end of the title poem. “I send to you a flame / like a bullet / repenting.”

Oh my god, you’re right!

When I finally figured out that line, I was like, YES, I can use this word! I also wanted the collection to end in a poem titled “Aubade”.

How come?

Well, first of all, I just really liked the word. But I also like what the form entails, which was a poem about mourning, that sort of either laments or celebrates the dawn. And while my aubade doesn't necessarily detail a certain morning, it does reflect upon a very significant point of change.

And you’ve been writing a lot of ghazals too, right?

Honestly, no. They’re too hard. [laughter] I've written two and a half, I think. Ghazals are SO HARD. Do you mind if I rant about them real quick?

Please go ahead.

The hardest part is the qaafiyaa, which is the internal rhyme that I know a lot of Western poets don't use. Typically, in a traditional ghazal, there's a bunch of unspoken rules that I'm gonna get to later, but the two most recognizable aspects are the qaafiyaa and the radif which is the internal rhyme and then the repeated end word. And those rhymes are really hard to come up with. They're really, really hard. I don't blame people for skipping out on the qaafiyaa, because, again, that's super hard, but it provides a really musical element to the ghazal that I feel has been lost in translation.

The ghazal isn't necessarily a form that originated in English. It was brought over by Agha Shahid Ali, I believe, who spent a lot of his life trying to bring over the form and its musicality. Because ghazals are often set to music in Pakistan, in India, the rest of the subcontinent, there's a lot of super lyrical language, a lot of internal rhymes, a lot of classical devices. It's just really fun to read his work! And I think that musicality has almost been, again, lost in translation when brought over to the West. When written in English, it's much harder to bring over that sense of musicality, especially in today's postmodern Zeitgeist or whatever.

I wrote one, like, a year ago. And I spent like a week slaving over it and then I just gave up. I couldn't do it.

Here’s a tip: if you’re writing with the rhyme, go to RhymeZone. Agha Shahid Ali only started writing ghazals in English after receiving a rhyming dictionary.

No way!

I mean, I'm so impressed, first of all, just by the fact that you wrote one, right? But then also the fact that you start off this book with it.

Oh my gosh, honestly, that was definitely one of the harder choices to make, because that ghazal has a very different tone compared to the rest of the book. It was actually Nat Raum, editor in chief of fifth wheel press, who actually encouraged me to put it right at the beginning. And I love them for that.

It has this feel that’s almost old-timey, but then there’s also this constant idea of fire and flames and stuff.

I like writing poems that I like, you know? I don’t really read Love Letters that much on my own, but I’m super proud of it even though I wrote it a year ago. Sometimes when I look back I’m like, “oh, NO!” There’s just so many craft decisions that I would’ve done differently. Especially “Have You Prepared For Your Death?” I feel like it’s a little on the nose now, though. I think the book’s almost wilder than my recent work, because there's a lot of variety in forms, a lot of hitting of the Tab key. [laughter] But yeah, I don't know. I think my past self has a lot of lessons to teach me still.

That's such an interesting thought. Like, when I go back to my old work, there’s a part of me that hates what I was coming up with at the time. Then there’s also a part that admires the naïveté and innocence established in those poems, and in addition the fact that I was somehow crazy and willing enough to share them with people. Also the fact that all these amazing smart people genuinely LIKED them. That will never not boggle my mind.

I’m wondering for you—like, in high school, sometimes I’d feel this pressure to be as good as the kids who were winning these fancy schmantzy competitions, and I never thought I was good enough until I somehow won one of them. But for so long it was like, I'm not as practiced. I don’t write like these kids. They go to fancy schools in America. Did that sorta stuff ever go through your head?

Oh my gosh, yeah. Fancy schools in America. No, I get you. Oh, my God, I’m a little bit bitter about YoungArts only being open to Americans.

Me too!

And even the Pulitzer Prize is only for Americans. Gatekeeping! Who would’ve thought? [laughter]

I know. It's frustrating. But I think you deserve to be as much of a part of the conversation as folks in the States, you know? Like, I loved your book. There's so much depth and longing and desire embedded within it. And so much natural imagery, too — stuff about touch and light and water and prayer and all this stuff. I guess what I’m trying to say is you’re kind of underrated.

Oh, thank you so much, man. Yeah, a lot of that I do want to speak on. Just as a person, you know, so much of the news is American news, and I kind of touch upon that in “Self-Portrait as Empty Mirror” which has the line, “I try to write about America / but it always ends as a portrait of something burning”. A lot of my favourite poets are immigrants, and I have a really weird relationship with that term. Not necessarily the term immigrant itself, but rather the fact that a lot of my favourite poets are Vietnamese-American, Pakistani-American, Iranian-American, Chinese-American. That suffix I think of really weirdly because I’m Filipino, I was born and raised in Saudi Arabia, I'm Muslim. But I was never called a Filipino-Saudi or Filipino-Arab. That distinction is almost what borders me from the stories of other immigrants and thus it informs my work in a sort of different way. I never really explicitly felt the pressure to be more Saudi or anything like that, because I was never Saudi from the get-go in this country.

But to add upon the whole America thing, I definitely do agree with you that so many non American voices deserve to be heard. A lot of my friends aren’t Americans and they're absolutely fantastic writers. Those words are weird to say. But yeah, with the lack of opportunities that America brings to non-immigrants and internationals, I definitely feel that there are so many voices that deserve to be heard and celebrated.

I really need to read more poems by non-Americans. I guess you’ll be my gateway drug for that.

I hope so!

Okay. That was a lot. I'm gonna give you an easier question. What's your favoruite poem in this book?

Either “Angel,” or “Study of Daylight,” one of those two. I was definitely really inspired by how then Danny [Liu, a former Significant Otter!!!] takes these super strange images and puts them in the context of toxic masculinity and stuff like that—the rhythm that he uses, especially in his poem “Wolf”.

I’ve also been writing a lot about faith lately, and I find myself coming back to “Study of Daylight”, thinking, how did I write that?

[laughter] Me too!

I wanted to ask you quickly about a couple other poems in the book, because there were lines that I couldn’t not bring up. Like this line in “Cuneiform”: “Maybe we call it longing because we define ourselves through distance.”

…Wait, what was the question?

Oh, there is none, I just wanted to tell you how good that line is.

Oh! [laughter] Thank you! That poem is a weird one. It was written at a time where I wanted to explore everything about desire. Romantic desire and religious longing, the yearning for a legacy. Ambition really informs my work to this day. [As artists] we get rewarded for being tortured. There's always the notion of the tortured, starving artists, that idea that we always have to be in pain. And I was thinking of what we give to be recognized. I really want to explore that in my later poems.

There's also this little poem that I don't think we mentioned yet, “These Days I Dream of Slow Dancing with Ghosts”. The title alone is really, really lovely, and then there’s just lines in here that totally wreck me. “Who could ever tell you / that you aren't already an ocean”. “Your memory a prism / holding onto the light / for never long enough.” “The truth is we are all immortal / except for our bodies.” DUDE.

I couldn't tell you how this poem came together. I think I just put together a bunch of notes app snippets and called it a day. [laughter] I'm just like, who wrote this? Because I don't think I know who wrote it.

I guess to bookend things, we can talk about the last poem, “Aubade”.

Yay! Honestly, it’s kind of corny how the last poem in the collection begins with the line, “this is how we wanted it to end.”

I noticed that too.

I think this was written almost as a turning point in the collection. So much of this book was written with fire as the literal end of the world. I mean, the title is Love Letters from a Burning Planet. But I think the first and last poems touch upon the reality of the situation. The ghazal parallels humanity to a wildfire. And then “Aubade” says directly, “O, how we live like a wildfire. How we wish to be rain / instead.” Because we generally see, and this book itself generally sees fire as destruction. There's the whole Avatar: The Last Airbender moment where we realize fire is life itself. It consumes, shines, burns, and then it fizzles out. “Aubade” was created as a sort of framework to hold that one line that we live a certain way, but in reality we're just part of the natural processes of this world.

And that final line, “I’m not sorry for making the world end, but won’t you come / and hold me anyway?”

A lot of the chapbook also concerns the author. As in, the speaker of these poems is an author themselves. In “Good Lord, Green Apple,” they literally talk about writing, they speak to one of their characters. In “I Can Make This Boy Live Again…” the speaker also reckons with memory. A lot of the chapbook definitely reckons with how memory is malleable, and because the speaker is the author in this collection, they're not sorry for how they choose to remember this person, because that's how it feels to them. The circumstances that led to this book sort of did feel like the world was ending. So I guess it's sort of appropriate.

When you were writing the book, did you have that title in mind?

The first title I had in April of 2022 was “A Dimpled Boy Told Me What Forever Means,” which is the first line of the title poem. But yeah, I was just putting together what I knew would be the title poem of the collection. I already had the order in mind, I just didn't have a title. There's a lot of love poems in this book, and then I had already written a bunch of poems about the world ending, hence “burning planet”. So that was the big epiphany that I had, and I felt so smart after that. It turns out there's a Tumblr blog already named "Love Letters From a Burning Planet”.

Oh, no!

I have to change the whole cover. {laughter] No, it’s ok. I don’t think I’m that popular!

Nah, that cover’s too lovely. Actually, you wanna tell me more about that?

Thank you! I asked my friend who’s an incredible graphic designer and artist. She gave me, like, 16 different covers.

[laughter] You’re kidding! So how’d you pick?

I sent all of them to my friends. I was like, “Make my life decisions for me.” And then I thought it'd be cool if the smoke on the cover made a face. It was honestly inspired by [the cover of] Everywhere at the End of Time, that Caretaker album I mentioned earlier.

How does it feel to be a real-life author with a real-life book?!

Oh, man. Unreal, still. It's not gonna come in full force until I have the physical copy in my hands, but it feels…half like being naked in front of everyone and half like yes, I can finally be famous! But also oh, no, what if I flopped? Honestly, I am so grateful. When I saw all the other people that Variant Lit accepted in that submission call. I was like, no way. Because I knew those people. I know Todd Dillard and Jessica Ram. They are incredible poets and I just feel so honoured to be amongst them.

But to talk about myself because this interview is about myself and I'm conceited—

[hysterical laughter]

It definitely feels terrifying and so, so cool. My favourite poet read my chapbook and slid into my DMs about it and I will be so annoying about this forever. I don't want to play into the cliche but this book feels like a miracle. This book was picked up in the last 10 days of Ramadan. My book got picked up and “Aubade” was announced as a finalist for the Dawn Prize in Poetry.

And Danny blurbed this book, as did Nat Raum, Sarah Ghazal Ali…

It’s incredible to think that they think this highly of me. Although they could all just be lying. It's one of my most irrational fears, that everyone's just lying about my book.

Let me tell you, I’m not lying. I’m a terrible liar.

It feels incredibly vulnerable, but I'm also really thankful to be, you know, among such great company. Sarah Ghazal Ali is my favourite poet. But you know how when a poet gets an acceptance, [they’re] like, “THRILLED to have received an acceptance from Atdadadadada, I am so grateful to be among such luminous company”? Extending gratitude to all the editors and stuff. It's genuine, but it's funny how everyone says it.

Do you have advice for people writing chapbooks, or for those who might want to in the future?

I always like to think of them as one section of a full length. I know I'm breaking my own rule by saying this because my chapbook has two sections. But the way I've seen a lot of chapbooks come together, especially some of the super short ones that are like 12 pages long, they’re super condensed and super intense and super focused on one subject. So I think if you want to write one from scratch, figure out what you're obsessed with. Or if you already know, then just start putting together a little collection that is super condensed and based on that one idea. And then you can branch out on that, because originally this chapbook had only 10 poems. But it was still 30-something pages, because of the long poems. I was encouraged by Nat Raum, and all the other people that I sent it to, to split it up. So I definitely do think that a good framework is to put together about 10 poems on one thing in particular. It doesn't have to be one theme, actually — it could be a chapbook of ghazals, a chapbook of pantoums. Don't be afraid to do something wild. I've heard Love Letters described as a mini full length.

I mean, if anything, it's definitely got, like, the scope and ambition of a full-length. It packs so much into such a tiny package. I can't want to see what you do when you start working with more pages.

Definitely, I think that’s honestly what a chapbook is. It’s something that has so much ambition packed into so few pages. And I've had this feeling reading pretty much every chapbook I read where I wanted even more. It almost feels as if the poems want to burst out of the page, because they have that much energy.

Mhmmm. Yeah. Like, I think there are ideas and motifs and lines in here that you could like write whole poems on, right?

Yeah. There's always the issue of pacing in a full length, you know, you can't just have banger poem after banger poem, so to speak. There's got to be quiet poems, and then all the weird ones. There's got to be some variety. But I think a chapbook definitely does give you a lot of space and opportunity to simply write on your obsessions and to follow your heart, right? A full length, you have to toil over forever, and I'm doing that [currently] and I hate it.

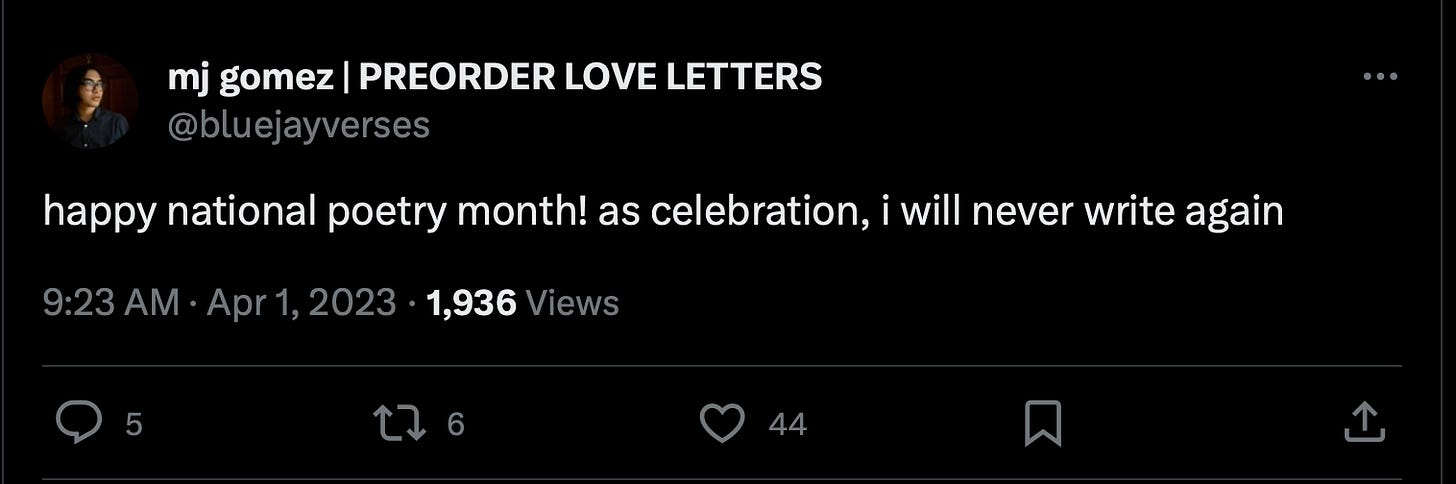

There were two tweets of yours I wanted to highlight before we wrap up. This is the first one:

I have so many tweets that are just, “guys, I forgot how to write”. And I'm feeling it right now. I'm on, like, draft 13 of this one poem. I'm just realizing how crazy that is [after saying it out loud].

And then you also inspired what I believe will go down as my best tweet of 2023:

I don't know why that's funny, but it is! [laughter]

I read your tweet and immediately thought of that joke. I was like, “I have to tweet this now.”

So, dude, what's next for you? Life-wise, writing-wise, whatever-wise.

I'm currently writing a full length collection. I've taken this whole year writing it and…it’s going, that's all I have to say. I only have 17 something poems in it right now. And it's really interesting how my voice has changed since Love Letters. And I guess I'll be reckoning with this throughout the entire journey of the full-length, in that I feel like Love Letters haunts me? [laughter] I sometimes feel that I've moved on, that I'm done writing about those particular heartbreaks, and then I wake up one day, and it's hard to get out of bed. And I'm like, oh, boy, I can already see the smoke of that cover.

Ask me the same question again later in the year. Oh, I also want to get published again. I need to submit more. I've been getting so many rejections.

I loved talking to you, MJ. Thank you for doing this with me.

This was so cool, Ottavia. You’ve got a whole community behind you. We love you a lot.

MJ GOMEZ (he/him) is the author of Love Letters from a Burning Planet (Variant Literature, 2023). His poems appear in Surging Tide, the Lunar Journal, Lavender Bones Magazine, the Dawn Review, and elsewhere.

and finally, if you enjoyed this interview…

what a wonderful interview and interviewee!! my favourite thing has to be how well MJ knows his poems. will definitely be looking forward for more interviews in this newsletter <3 thank you