Significant Otters: Ivi Hua

Dissecting marching bands, Young Poets Workshops, and Body, Dissected (kith books, 2024).

Significant Otters is an interview series exclusive to Things You Otter Know, featuring wide-ranging yet casual conversations with writers about their new books—writers who (most importantly) happen to be Otters. Significant Otters, if you will. To learn more, click here.

My last Significant Otter was MJ Gomez.

A full archive of interviews can be found here.

I’m looking to schedule interviews with authors with books out in August 2024-onward. My website is in the process of reconstruction; in the meantime, please contact me at ottaviapaluch@gmail.com. Follow up if I don’t get back to you after 2 weeks. Interviews are currently unpaid until I launch paid Things You Otter Know subscriptions in winter 2025.

Our first Significant Otter of 2024 is Ivi Hua, the author of Body, Dissected (kith books, 2024). Hua is still in high school, but both her and her poetry are incredibly articulate and wise well beyond her years. Get excited to watch her grow and prosper in the years ahead.

I spoke with Ivi over Zoom back in March, but we first spent months trying to wrangle our PST (hers) and EST (mine) time zones together. We primarily spoke about her great debut chapbook, but there’s many other tidbits in here that I’m excited to finally share.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Important links are provided at the end.

TYOK: It feels like we’ve tried scheduling this conversation more times than your book has pages.

IVI HUA: No, you're good. We're just busy. I feel you.

That was my terrible lede into me asking where you're calling me from.

I’m on the east side of Washington. It snowed yesterday, and now it's completely sunny. The weather has been completely out of whack. Our entire January felt like spring, and then we hit March, and it's like, “okay, it's snowing every other day now.” I like sledding, I like ice skating. But at some point it gets really dreary. I’m like, “when does it end?”

I guess since you brought it up before we started rolling, we could start with you telling me a little more about Young Poets Workshops.

I could talk about YPW for hours. I write so many branding emails, so many grant applications. We’re a digital online international community. We're based on Discord just because it was, like, free. And because it's easy. We're just working to bring new connections, a new generative community, where writers can just be writers and writers can just interact with others around their age. When we first started it, we were kids. And now I'm really glad [we did], because I think it's fostered such a positive mindset in the community.

I think teen writers nowadays are so pressured to be an Adroit Journal Summer Mentee, or get into the Kenyon Review or whatever, and accomplish these grand, huge things. And it's just really nice to have a space where we can support each other versus competing with each other. Jenna Nesky, Fiona Jin and I were all in the same Adroit cohort and realized we wanted a community for everyone. We're trying to create resources, we're trying to make the space more equitable, and more like a home versus a competitive place for you to get your trophies or whatever. So that's my spiel.

So what's your role in this?

[The three of us are] the executive team. We meet once every two weeks and work on everything from grant applications to moderating the server. We send out the emails, we go for grants, which—thankfully, we've been really honoured to be a part of different grant cycles—and we have money, we have money! Which is really helpful. And we do the outreach, and we’re trying to pay more and more writers. So we're responsible for planning events and making sure that the community runs smoothly as a tripartite executive team. And we also have our lovely graphic manager, Anna, she's super cool. She does all our graphics.

So does the grant money go into…paying for Discord Nitro?

[laughter] No, actually. We use it to pay our panelists and our writers. We had a YoungArts panel earlier this year, for instance, and we paid each of them. And then whenever we bring someone in for a book club [event], we release the digital PDF of the book into the server, and then we bring in the author for a Q&A and a reading, and we pay each of those authors. So all of the money we receive goes straight back into the writing community, whether it be through payment, or through facilitating events. We spend some of the money on, like, Zoom Pro, and stuff like that, though.

Keep it real, man!

Oh, my God. Yeah.

I love that you just keep innovating and keep pushing the boundaries of what a little online community like that can do. Which is so cool. It's so amazing that y’all have taken it upon yourselves to take initiative. I mean, one of my regrets is I didn't even get involved enough with that community when I was younger. I was mostly just Tweeting into a void. Part of why I started Significant Otters—and why I’m so happy to finally have it back—was to create that sense of community with folks like yourself, right? To show young people that there's kiddos out there like you who care, who are there for them, right? And so I think our values align in that regard.

I'm really proud of how far we as a community have grown and flourished despite the odds. It’s really great.

And speaking of great things. Your book.

My book.

Initially it was meant to be a micro. I put together maybe 10 poems max. I thought oh, it'll be my little micro project, and then Kith opened up its speed run. And I wanted to be a part of it, I want to do something with this book, and I also like instant gratification [laughter].

So I started piecing it back together, and then Ktih somehow shortlisted it. And I'm so honoured to be working with them.

As we moved [forward] in the process, when we started talking about binding and stuff, they were emailing me and they're like, “oh, you need a few more pages to do perfect binding.” I wanted my book perfect bound. I thought it’d be so fun. So I dug some poems out of the archives, I wrote maybe two new poems, and I slapped them in there. It wasn't that there was anything inherently flawed, it was just that it didn't make page count.

You mentioned that it started as a microchap. How did that initially come about?

I was in marching band my freshman and sophomore year. And this sounds like a tangent, but it's not. Because to be in marching band leadership, you have to accomplish volunteer service and a special project. At the time, I was in my freshman year. I kind of just sat around and wrote my silly little poems and I did my schoolwork. So I was like, okay, I'll put together a microchap. And I did get into band leadership. I also ended up quitting marching band the next year [laughter], but it brought us the book, okay?! I submitted it to a few places, and it got rejected, but people were telling me it had potential. Up until that page adding thing, I was trying to find more ways to add more nuance and make it a more fully fleshed out book.

There was a really long period where I just sat on the book, and I did nothing with it. And I think that's honestly what gave it so much substance because a lot of the poems, the big bingo poem in the middle of the book, was written way after the initial microchap was started.

It’s all over the place, man.

It’s really doing everything. But at the heart of it, it feels like a rich, vivid blue. And it's a lot of emotion put together. When I was writing it, I tried to hold it together by memory and by love in all its forms and by body parts and what it means to take yourself apart and put it back together.

I think it's about the ways that both memory and emotion inhabit our bodies and how humanity processes all these emotions of love and grief and memory, both physically and also through ideas of metamorphosing. Dissecting the body to build a whole that's not entirely cohesive, but all strung together by the same same thing. And I guess that's humanity.

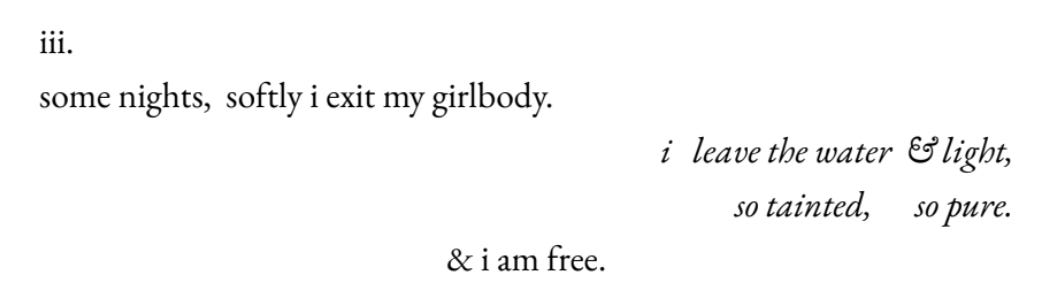

There’s this big moment in “girlbody,” where you write:

That for me is a big, big, big, big shift. I wanted to see if you felt the same way.

That's the first moment where the dissection actually occurs. There’s nothing [before this poem] about the body as an inhabitable space versus the body as just a thing you have to live with. That poem is the moment of choice, it is the turn. [The poem] right after it, “memory nonlinear,” is physically split into 25 different squares. That is the moment where the disjointedness manifests itself on the page. And then, of course, I do have a poem literally entitled “disjointed”. Those middle three are all really important. I tried to concentrate the ones that are in the middle, and I wanted to end with “let us erupt in feathers,” because that poem to me was always about my girlhood and wanting impossible things. It felt like an appropriate way to end the book.

One of the things I found really interesting was your use of italics. When and why and how the speaker turns inward and all of that.

When I first started writing poetry, italics were used for what would not be said directly. It was more of the train of thought. Because I always thought that in my poems, the normal text is just direct, just there on the page. Italics almost waver in a way that makes conducting disjointed thought, and thought that’s not entirely conjoined, or thought that's entirely willing to be set directly out in italics. “girlbody” is the biggest instance of where I just insert italics everywhere. There's this disjointed, super spaced out thought train full of repetition. In that poem, italics just feel closer to the heart of the poem, whereas the normal text is dictating the reality. The italics represent what is unsaid, even when I am saying it. It's a means of conveying what is meant to be internal, versus what is meant to be external.

There’s a really deep connection in this book between the nature imagery and the theme of girlhood. How did you get those two things to coalesce so seamlessly?

You know those memes where they're like, “all a girl needs is to sit next to a body of water”? [laughter] That's not where it came from. But you made me think of that with the girl and the lakes and the cliffs.

I've always really admired nature. I've admired the simultaneous beauty and the simultaneous force of nature. And the more I grow up as a woman in today's society, the more I realize that's what I want for myself. I want to be who I am and I want to be able to hold power by the means of my own achievements. I think a lot of that desire to honour nature and to bring out that admiration and that sense of physicality for my poems definitely wove its way through the book. I was trying to create a poetic landscape almost subconsciously. I think ancient memory, which is a huge thing that this chapbook is about, each memory is rooted in a specific place. Each of these poems, they have their places and they have their times. And I think that's definitely what sparked a lot of that nature imagery, because I wanted to flesh out the idea that these moments are grounded in something, whether it be the sky, or just this idea of a wasteland.

So when we go back to the title of a body being dissected, where did that title come from? Why not call it body in a river? Or body jumping off a cliff?

body in a river! [laughter].

I wanted it in pieces, if that makes sense. When I first did the microchap, I was a kid, I was just messing around. But there's always been this innate sense of disjointedness in my poetry. Rough edges, almost. And I wanted to reflect that this body was not necessarily whole, but it was together. And there’s something to be said about my own mental health at the time [laughter]. But growing up, I definitely struggled with body image, that kind of thing. And so there was this really strong idea of girlhood and bodies and taking yourself apart, in an attempt to become a societal definition of whole. We're getting deep into the metaphors here. But yeah, I think writing is how I wanted something to convey that it would be in pieces, but it would still be in some way a whole, right? And that's, as you reference to, is kind of what it’s like. The poems, they jump across space and time and form and language—and somehow they're all here together, bound together by their common threads.

You bring up that sense of disorientation throughout the book. Where I noticed it the most was in the last poem. It feels like a play or dream or reverie or something. And there's so much cool stuff happening.

“let us erupt into feathers [tangible things]”. I thought I was so funny when I did [the title with brackets]. I was like, “look at me experimenting!” I think it’s literally a dream. Like, not one I had, but running through the scenes—the girl dreaming wakes up and she’s like, “let us erupt into feathers in the mirror.” I think she’s chasing some semblance of something you want but can't have. It's one of the early ones that I actually thought was good. At the time, I had a lot of wants and unfulfilled emotions, as I'm sure is a universal experience, especially for teenage girls, right.

Big time.

And I wanted to put that somewhere and I put it into this girl, the dream girl. And then there's this girl dreaming of the dream girl. It's cyclical, in a sense, because she's chasing after someone she wants, whether to be or to be with. It's hard to tell throughout the poem, but it doesn't matter. Because in the end, they're one in the same. It's kind of an inversion of sorts, of this kind of raw want and desire that comes with growing up, and just wanting to be good and to be something so free, to erupt into feathers, and chasing after that. I put it at the end because there's such a connotation of both freedom and of dreaminess that carries throughout the book.

Were you thinking of Emily Dickinson?

That's a good question. I want to say no. I can't be 100% certain because these influences are so subtle. Possibly, because I read a collection of her poems fairly recently.

She’s cool, eh?!

Yeah, she is.

You mentioned the speaker dealing with all this stuff, right. I write poems from a very personal place. What was it like writing poems from the perspective of a speaker that is not yourself? What does that feel like? Especially a whole chapbook of it.

Some of these poems are me, I will admit to that, but some of them are also an augmented sense of self, as if [I were to] I remove me from myself and just leave the raw emotion and desire, and that's who I'm speaking from. Some of them are calling upon ideas of people I could have been. The emotions are mine, but there's also that sense of me trying to to be connected and empathetic with the world and to understand the world’s emotions as a whole, like the people around me. A lot of the poems I write are also trying to make sense of very human emotions that transcend across individuals, and I tried to convey that through the speakers who aren't so much defined as they are felt.

That is so cool, dude, I resonated a lot with that, especially the empathy part. That you can write from a different place but still experience those feelings and bring them into your work. What you're doing craft-wise is very exciting.

How does it feel to be a published author with a real life book?

It's actually insane. Like, I don't know how I got here. I am continuously just like,

”is that really me?” [laughter] I've always been a silly little writer. I made those little stapled books in, like, first grade, and I’d write about kitties and stuff. And it's just really great to see this dream come true.

Writing has always been the sole thing that is just my own. Like, I do it because I like doing it and I like reading it and not because there's any outside expectation.

But what has writing this chapbook taught you about craft? And I guess in reverse, do you have advice for folks who are writing chapbooks or who want to in the future?

It was kinda wild for me, because the pieces just fell into place. I put together the version I submitted to Kith maybe the night before it was due. And before then I hadn't touched it in months, at least. My best piece of advice is to continue doing the things you love, do what feels right—and then when the time's right don't be afraid to go forth and do it.

In terms of craft, I've learned a lot about what it means to have poems [cohere] together. And I’ve learned to trust my own intuition, letting my writing be more intuitive, and following the lines that it wants to lead. I think it was Avery Yoder-Wells who said that poems tend to return to same few themes over and over again. I've learned to allow myself to let my poems go where they want to go.

What’s next for you, book-wise, life-wise, whatever-wise?

I'm just gonna continue doing what I do. I want to continue making YPW stronger and just building new community and learning and growing along the way. This summer, hopefully, I’ll be writing things. I will WRITE, I will CONSISTENTLY WRITE.

Manifestation!

And I would love to put together another chapbook. I think chapbook number two is the long-term goal for now.

That’s so exciting!

Yeah! Now I know that I can do this. It might be a little edgier. I don't know if this is my teenage phase or whatever, but we'll see how it plays out. I just want to keep connecting and learning from cool people like you.

I don’t wanna ruin your band practice, so we’ll end here, but thank you.

Thank you!

IVI HUA is an Asian-American writer, dreamer, & poet. A Pushcart & Best of the Net nominee, she is the author of Body, Dissected (kith books, 2024) and cofounder of Young Poets Workshops. Ivi believes in the initiation of change through language, & she is overjoyed to be a Significant Otter.

Follow Ivi on Instagram here.

Purchase her book directly from the publisher here.

Learn more about Young Poets Workshops here.

Share this interview: