This is Ottavia Paluch and you’re reading Things You Otter Know. Hope you had a candy-filled Halloween. Welcome to the October/November 2022 edition of Significant Otters!

For those of you who are new here, Significant Otters is my monthly conversation series with writers who happen to have books dropping and who (more importantly) happen to be Otters. Significant Otters, if you will.

ICYMI, last month I spoke to June Lin:

Before that I hung out with Jessica Kim and Stella Lei.

NEW TO THE COLUMN: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book (or if you’re someone who knows someone who would enjoy talking to me) reach out through my website and let’s get you some free publicity!

This month’s Significant Otter is the coolest dude on the block. I spoke to Daniel Liu (he/him) in mid-October over Zoom from his home in Orlando, Florida. Liu is a poet you should keep your eye on. His work has an emotional depth and maturity that belies his age. He writes about guilt and innocence and intimacy in a means that is fresh, powerful, and necessary.

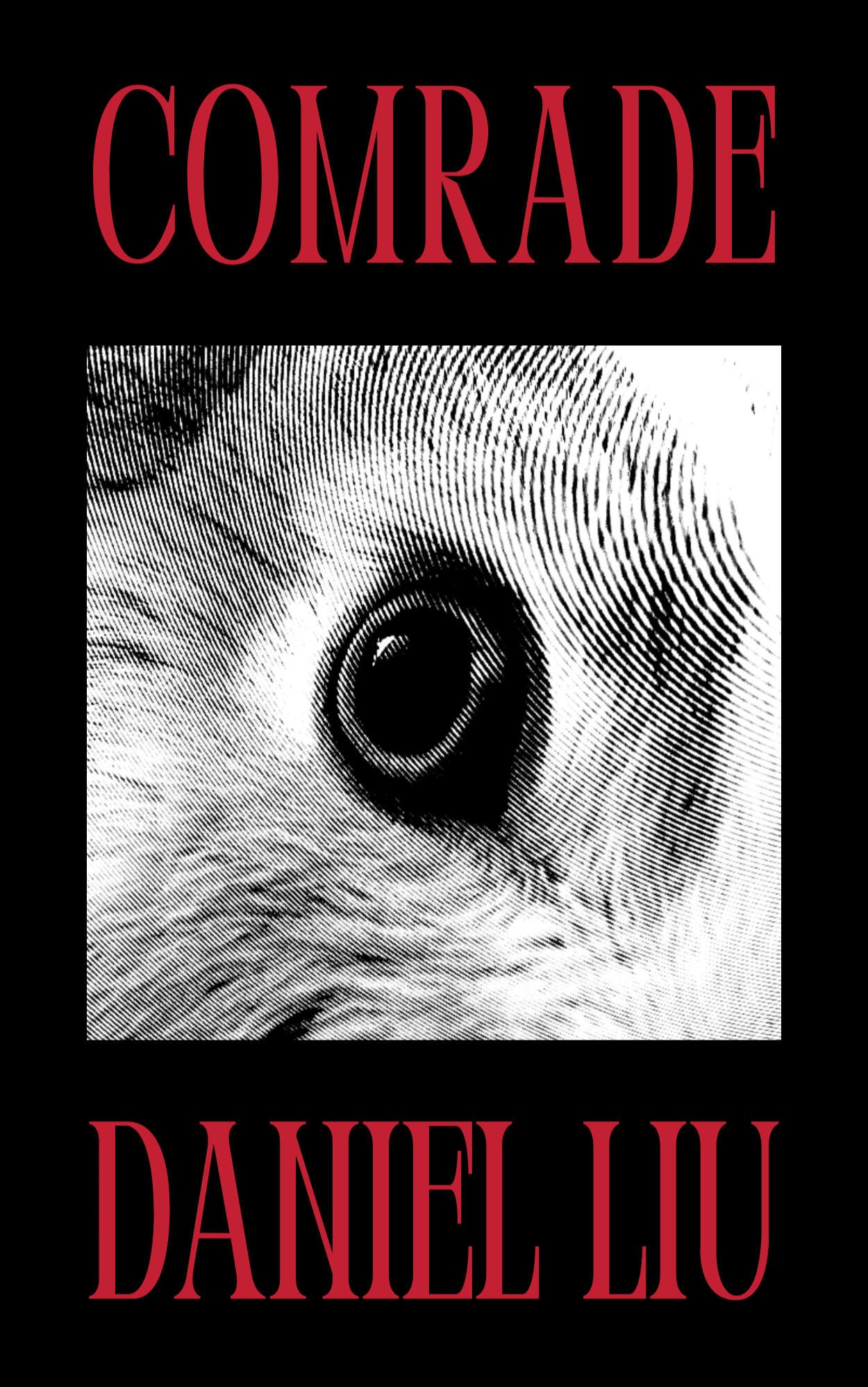

I spent nearly two hours with Danny, where we talked poetry, gossiped, and laughed our heads off. We spent a ton of time discussing his debut chapbook, COMRADE, out now from fifth wheel press, but our conversation was all over the place in the best possible way. I feel very lucky that I get to be this guy’s comrade. (Sorry, I had to.)

This interview has been edited for length and clarity because Danny is a debate kid.

🦦 —O— 🦦

OTTAVIA PALUCH: You know, I’ve never met anybody from Florida.

DANIEL LIU: I feel like we’re a pretty obnoxious group of people. The weather’s very spontaneous. I can’t complain much about it. How’s Toronto?

I mean, I’m in a suburb of Toronto, but I love Toronto itself. You should come here sometime. It’s lit.

Really? Do you like it?

I like the city. I don’t like the suburbs as much. It’s boring. There’s, like, a Tim Hortons every 5 meters.

What’s a Tim Hortons?

They’re in the States too! Maybe just not in Florida. It’s like Starbucks, but Canadian, and cheaper, and not as good.

How come?

It’s…I feel rich when I get Starbucks once a year, you know?

Five dollars for a cup of coffee. Ridiculous.

Oh my god, we’re getting so off topic here. ANYWAYS. About you. Give me the lowdown on how and why you started writing.

I think a lot of my writing started with me just wanting to make something, anything at all. I was the type of kid in elementary school that would, like, throw mud and plants and weird weeds together and make potions, you know. I feel like I've always had or been in love with creation, in that sense. Wanting to make something physical out of anything, even if it had no actual value to society at all!

But I've done art in the past. I did art lessons when I was a kid. I liked it, but not enough to continue. I've always kind of kept that creative side in me. In freshman year of high school, I started actually putting my thoughts on paper. I started journaling, and then I was like, “Yo, I have a lot of feelings on the inside. And I also, like, think, and I can put that onto paper.” And then it turned out to be something cool. And then I got on Twitter, and then I read, and then I was like, “Oh my God, these kids are fighting for their lives in the creative writing world.” It sounded kind of cool. So I kind of got started on my way to creative writing through immersion in art.

Who were the writers you turned to then?

Siken and Vuong. Obviously. Steven Duong and Aria Aber advanced me too. I’ve been turning a lot to contemporary poets. I’ve very rarely looked towards old poets. But one of the first poetry books I ever read was T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Read through it like it was a novel. The only thing I learned from it was that there was a remarkable sense of language, and that I was supposed to believe that this language was supposed to be elevated and help me somehow. And that kind of philosophy towards poetry—language that you believe to be elevated—has really influenced how I write.

The only thing I know about T.S. Eliot is that April is the cruellest month.

APRIL IS THE CRUELLEST MONTH!!! YES! “Prufock” is literally just…an embarrassed and humiliated man telling a story.

Oh, so you can relate.

THAT’S WHAT I’M SAYING! Masculine accumulation. Though I think I understand the frame of reference from Ocean Vuong a lot more than I do for T.S. Eliot. And I think that’s fine, right?

…How are you coming up with these great answers so quickly?

Everything in my head just…pours out of my mouth.

Are you a big talker in class?

Yeah, I’d say so. I try as much as possible to interact with the ideas—for me to learn anything, I have to.

And when you walk around in school, knowing that you have a book and all the kids around you don’t, *laughs* how does that feel?

I think everyone at my school has their own speciality. That’s what’s so amazing about the environment I’ve had the privilege to grow up in. Everyone cares about their own things and also about what you’re doing. It’s cool seeing other people achieve in their own fields. Same thing with my book - it gives me an aspect that I care about and shows my interest and care and attention.

We've talked for what, ten minutes? And this whole time, you’ve been so humble, and…you care. You care.

Thank you for saying that.

You wouldn’t get that idea from your Twitter, though. Oh my god, we have to talk about your Twitter before we talk about your book.

Oh my god. I genuinely use that space as a void.

I see it more as a shine to Steven Duong.

That’s exactly what it is. Everything about it has been geared toward that kind of kind of mindset. I like what Steven almost represents to me, you know, because every time he posts something, it's always an American cowboy Buddhist in America living his best life. The idea behind that fearlessness and courage—that's what I strive to be. And I want that in my own life. That's why I obsess over him.

When I met him at Iowa [Young Writers Studio] I was about to cry. My instructor came into the room and was like, “I have a surprise for you.” Me and my friend looked at each other because we had discussed Steven with each other [and with my instructor] before. I could see Steven’s face through the little window in the door, and I squealed so loud. By far the highlight of my life.

And about your tweets, since we were getting to that, there’s one tweet of yours I wanted to highlight:

This was coming from me having to write an English paper, I think. I was having trouble trying to explain what I was going to talk about. The problem with that as a poet is that poetry itself kind of approaches the infinite, the unknowable, the literally indescribable through what little concrete pieces we have. In order to fully make a sentence, you need a noun and a verb. And to be honest, most of the time, I can't find those things, especially in terms of abstract ideas. So when I was writing that paper, I was literally unable to formulate what I had in my mind onto that paper without using [abstract] terms.

I like to imagine poems as encircling something, like a pack of wolves around a deer. So you have to like go around it. And then you have to close the circle and close the circle until you get to it. But you can never really get to the thing. And for complete sentences to work, you have to say the thing, because that's what's expected of you, especially for literary analysis. I was reading this essay called “Against Explanation” by Tarfia Faizullah where she talks about this poem she wrote called “100 Bells”. It features a lot of pretty heavy imagery and traumatic events. It was sort of a jab at people asking her to explain the poem, like, oh, did this really happen to you? Is this a real thing that you experienced? Why did you write it like this? And in the entire piece, she kind of dwells on this idea of, why is it the poet’s job to explain why? Why is the grieving done on the side of the poet? I think the idea behind why poets cannot write prose is because we're trying to give the reader the pieces they need to formulate their own dissection of the work.

Dude. That was excellent.

Thanks!

There was a part of your writing story that I forgot to touch on earlier. In between you writing this book and getting it published, you won that contest for the Incandescent Review that I had the honour of judging along with Esther Sun, who is just the best. We read submissions blind, and when we came across your piece, we were like, “holy shit, this kid!” It felt amazing to have that privilege and honour of rewarding kids like you who really, truly deserved it.

And at the end of the Zoom, one of us—there were like 6 of us—was like, “I hope none of the winners plagiarized!” It was so funny.

Oh my God, if you're writing for the merit stuff, it's really not worth it. Like, it's a disservice to yourself, honestly. Because the whole point is for you to grapple with these things and to understand these things through your own frame of mind. What help is it to just copy?

I know, right?

So, like, your book. Since that’s why we’re here. How long did it take you to write?

I thought a lot about this book. I’d have 50 tabs open, a notebook by my side, searching up different words that could be used in different contexts. But I think this book was done in two months. They were all unpublished at the time, and they were done in a series. So each poem informed the other. And that was important for me, because I wanted it to have a central kind of dogma that it always followed. And that required it to be done in a shorter timeframe, because I was in the same state of consciousness for all of the poems. fifth wheel press was so, so helpful in honing my vision.

It was a very spontaneous decision, as are most of the things I do. But the idea came up one night and I was like, You know what, I have to write this. And I did, and now we're here!

I’m so glad we’re here. This book is fucking good. Like, DUDE.

You know, I try to send my guests a list of poems that I want to briefly touch on, because I don't want them to be overwhelmed when I ask them about a poem so they don’t go, “Oh no, I forgot what that poem was, I forgot I even wrote it.” Narrowing your book down to a few poems was so tough. Like, how do I pick?

I’m really happy you said that.

I think there’s just…a real sense of craft. I can tell you've worked hard on this. I can tell it like went through bone-crushing edits. When I spoke to June Lim last month for this column, here’s what she said about you:

“I feel like the people I’ve met on literary Twitter have actually been a big influence. I’ve learned a lot about writing poetry and what I liked in poetry from reading people’s work that we were friends with on Twitter. Like, we were talking earlier about Danny - how he’s so efficient with his words. I was trying to write shorter lines because of his influence.”

I totally agree with that. That’s the perfect word to describe your work. Efficiency. It's like every word has 25 knives attached to it.

Aww, that’s so nice! I’m really happy that June mentioned that. It makes me feel like I’m a writer, you know what I mean?

I think this word gets overused in a lot of literary circles, but impostor syndrome is so real. You get it on every level. Because you’re putting stuff into the world, and you’re scared that it’s garbage. But if you believe it’s worth it, then it’s worth it. That’s the end-all be-all.

Oh my god, this book is so worth it. What would be your elevator pitch for it?

I wanted to write something queer, and I wanted to write something personal to me. And I wanted it to be dark and I wanted the word “comrade” in it. I knew the title before I knew anything else about this book. There were these elements in the book that I wanted of violence, of cruelty, of family, of relationships, of…rabbits, for some reason? I really emphasize this image of the small, innocent animal in this collection. The ideas behind this book were really a wide assortment of images in my head and an idea to write about a personal history that I encountered.

When you sent me a e-copy of this book, I was thinking, “okay, COMRADE, this is going to be a nice, happy book about friendship.” And I read the first line, and I’m like, “oh, shit.”

*laughs* I like that double definition. That’s what drew me to it.

Whenever I do these interviews, I love to ask writers about the first and last pieces of their book. Now it’s your turn! Tell me a little bit about “Headwaters”.

The idea of headwaters is the place where rivers start, and this is where the book starts! It’s kind of corny but I like it because this book deals a lot with inheritance—inheriting violence and cruelty and conflict with the world. This first poem is about the speaker’s father. And that kind of works to its advantage because it puts everything in very animalistic and primal terms.

The start of everything, is, in some way, violent. The world began with very primal tendencies, this almost brutal tenderness. In order for anything [to come into order], it has to deal with itself and grapple with itself. And from that violence, you can create beautiful things.

For example, the Big Bang! Horrible things are happening because nothing is completely still. Everything is hitting and colliding. Conflict is being created. But from that space, you can build your own type of future. And the idea of a headwaters as a place that begins but does not finish was important for me, for this starting poem. It introduces family conflict and this idea of what it means to be a son to something. To be the descendent of something. Incorporating these ideas of violence and inheritance into this universe of horrible violence.

I think you might be muted.

Thank you!

Speaking of sons—there’s a poem in here about sons. Actually, there’s a lot of poems in here about sons—I really should specify! *both laugh*

The thing that struck me about “Field Guide to Rabbit Hunting” is the space it provides itself. Every line is on its own. Every image, as brutal as it is, has its own space. We were just talking about the Big Bang—every line in here feels like a tiny nebula. The last two lines, “Son everything around us is set to burn / Son this rabbit is only a rabbit because you can kill it”—are such gut-punches.

This poem specifically was trying to explore the intersection between guilt and innocence. There’s a lot of fear in family dynamics over who’s to blame, about who the guilty and innocent are. Why’d you do this? Why’d you do that? And it’s easy to defend the side of the innocent. It’s easy to always say that whoever’s innocent is always correct. But there’s also this consideration: the other side believes that they’re innocent, too. The consequence of innocence may be that other people find you as prey. If you are vulnerable to the world, there are people who will treat you negatively. For this poem, knowing how to traverse that space, that landscape of danger, was really important for me to examine, especially [within] a family dynamic.

I think what’s also really impressive about this collection is the versatility. You’re doing all sorts of stuff with enjambment and stanza. I look at something like “Cradle Theory,” how every indent is really considered. There’s this edge to it.

This poem focuses on the very centre of the relationship between the father and the son, what it means for the two to combine. And I like couplets. They feel the most natural to me. But I also wanted the actual enjambment to mean something to mean. It held a very symbolic space between the lines that I could explore distance in, but also a sense of intimacy.

There are a lot of misnomers in this collection. And I’m fine with that. It feels correct for me, and that’s all that matters.

Yeah, like, who cares about my opinion? *both laugh*

And then the lines, “Knees forever scraped / Arms always open”—that contradiction is, like, “ooh,” you know?

Again, it’s the idea of innocence at play. The most innocent thing by human standards is a child that has done nothing wrong. And it’s this idea of guilt and harm that’s been put onto them.

Also the last line of this poem, “We are so / childlike, Ba almost forgets we are boys”.

I was trying to—here’s a debate term for you—I was trying to brightline. I was trying to find the point of no return, where you are a boy versus where you are a child, the difference between these two. Trying to carve out definitions for them that are rooted in guilt and innocence.

And then we get to the title poem, the longest poem in the book. It reminds me of “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous,” the Ocean Vuong poem.

I have a real connection with Ocean Vuong’s work. We come from very similar backgrounds and we come from similar writing backgrounds. When I grew up, I was in ESL classes. The majority of my family is illterate—they did not graduate high school, or even middle school. So the fact that I’m still in high school is lowkey kind of rocking. We share a similar set of experiences that we both draw from.

I like this extended metaphor of the comrade. I think it demonstrates both sides of the coin—the violence of something and the love you can hold for something. It holds historical associations with war and violence, and from that space I can draw my own meaning. I can use those definitions to create my own. The epigraph is important to me [because of that].

I love how you’re in conversation with language.

Thank you.

And when you write, “There is always another / city to count. / Another swimming pool. // Another hour. // Another pair of hands. // Another calling,” I read that as hopeful. But I’m not sure if I’m supposed to.

The last line in the last poem of this book is literally “Forgive me.” That’s just as hopeful as this. Trying to label these parts as such is a thing you can do, but how they interact with each other is a lot more important. That’s a really dark part [of the poem], but it leads to a very hopeful part. Which is immediately followed by a darker part. How does that make you feel? How does that encapsulate or explain something? How does that approach the infinite, the unknowable?

You started asking those questions, and in my head I’m like, “…do I have to answer these?” *both laugh*

And I just love how the “Forgive me.” stands on its own. It feels like…it feels. It FEELS. I think that’s gonna be my answer to everything now. If someone asks me how I’m feeling, I’ll be like, “I don’t know, I feel.”

That’s why I love poetry! Because you do seriously just feel. I like reading poems that way—feeling through them. Analyzing them line-by-line, stanza-by-stanza: that’s a good way to understand why you feel, but you’ll never get to the bottom of it. There are some things that are truly unexplainable, and only made apparent through poetry.

Exactly. I’ve interpreted these poems my way, but they also feel very personal and true to you. Your interpretation of your own work is gonna be WAY different than your fans, your Liuvians. *both laugh*

I like that idea of multiple interpretations, and all of them being true at once. That is what poetry requires. I remember someone saying that half of poetry is the poet’s job; the other half is the reader’s. I think that’s so pretty.

You know, sometimes I read poems and I feel dumb as hell. And part of the reason I started Significant Otters is to learn from poets that I admire and feel like I could do it, too. Because sometimes I’ll come across work and wish I could write like [someone else.]

I think the more useful path is to develop your own brand in terms of how and what you write. My instructor at the Iowa Young Writers Studio was like, “It really does not matter if you publish, whether you’re 15 or 40 or dead.” *laughs* Like, some people get some books off when they’re loooong gone!

F. Scott Fitzgerald!

Yeah! But the idea is that you’ve developed a style you can confidently say, without anyone telling you, is good. That’s all that matters. You can read every poetry book and imitate those poets, but your writing won’t be good unless you believe it is.

This last poem, “Fujian, 2005”—it’s a poem in the form of a letter.

The epistolary form is interesting. It requires a level of intimacy to the work. You’re writing to someone, they’re on the receiving end, and you are giving a piece of yourself in your writing to that person. Except this letter is on display for everyone! So that level of intimacy is thwarted by…everyone else. But it’s still meant to have that intent of intimacy. It felt like a conclusion paragraph, almost. There’s another poem in here called “Fujian, 1979”—my father’s birthday. And 2005 is my birthday. So—

Oh, THAT’S why! I thought you were choosing random years, or because they signified some big, historic event. I didn't realize the big, historical event was you being born!

*laughs* That date part was important to me because it felt inherited. I’m inheriting a place—Fujian—from my parents, and I’m also inheriting myself from them, too. I’m diving into the inner workings of this collection, trying to approach the unknowable, the unthinkable. The poem required intimacy; that’s why it’s a letter.

You know, in my experience, the best ending poems stick with me long after I’ve read them. I think this poem is one of those. This passage specifically at the end, where you write: “Ba, I am a son that is / engraved with other sons. // All light goes on inside the body. / All bodies go on.” Like, SHUT UP! You’re KIDDING.

*laughs* I took a lot of creative risk with this collection. And I really tried to write what I wanted to write. Seriously. I wanted to write what I didn’t see and what I thought could be. I was SO ecstatic when I wrote those final lines. But then two weeks later I was like, “this is actual shit. Why did I write this down?” And then I reworked the poem and I loved it [again]. Language is applicable in every single possible scenario because of how volatile it is. It requires different interpretations at different times. Even though the words themselves may not change, the thought behind them always does.

No, yeah, of course. You mention how you’re essentially in conversation with your father in this poem, and then you say, again, “All bodies go on.” It makes me consider [the idea of] legacy, and the word you mentioned 25 gazillion times, “inheritance”. It’s powerful because it’s personal and, again, so intimate.

And now, having had this conversation with you, the 3 things that stick out to me about your poems are how personal they are, how intimate they are, and how powerful they are. I think that’s what you wanted. That’s what every poet wants.

I wanted to write a book I would read. That’s what this was.

And not that you can feel joy reading such a sad book, but when I was reading it for the first time, I got so excited, like, I can’t wait to talk to him about this. I have so much to ask him.

I’m similarly excited by the fact that you’re only 17, and you have so much growing to do.

EXACTLY.

And when I say that you have so much growing to do, I don’t mean, like, oh, you suck. Because you don’t. It’s more of that there’s so much ahead of you, poem-wise. Not to put pressure on you, but you…you’ve set the bar high. I cannot wait to read the work you’re creating at 27 and 37. I hope you’re still around writing poems like these. Maybe you’ll decide to write COMRADES II: AMIGOS or something.

*laughs* I do like that idea! Hahahaha.

I want to wrap up with a few questions that I’ve asked pretty much every guest here on Significant Otters thus far. While we’re still on the topic of your book, you did the cover yourself. Which I’ve never seen before. Except on Wattpad.

I founded an arts collective called INKSOUNDS last year and learned Photoshop for it. Plus I run social media for a lot of stuff, both in and out of school.

So that’s why your tweets are so good! You cheated!

*laughs* I literally have a bunch of artistic things that I try to do. Sometimes they work out and sometimes they don’t. But my cover is a rabbit’s eye. The idea came to me after 5 hours of making bad cover art. I just decided to keep it simple. I like the red lettering. And with the photo, I wanted it to convey the…the fear that I wanted my readers to feel! *laughs* And I was like, “you know what would make this absolutely terrifying? If I just zoomed in on the eye.”

It looks like something that would be in the horror section of a Chapters. Or, sorry. Barnes and Noble. I forgot you were American.

I don’t know what a Chapters is.

It’s like a worse Barnes and Noble.

Why is everything in Canada a worse version of something?

That’s Canada for you! Except for healthcare. *both laugh*

Seeing as you’re someone who has recently been racking up a ton of Ws, what advice do you have for people like me who haven’t been racking up a ton of Ws?

That it’s all subjective and it doesn’t really matter at all. The reason I do any of those things is usually because I feel like I need to prove myself. But it feels hard to forgive myself of that, to give myself that level of trust. You should focus on writing entirely for yourself. If you keep developing your style of writing to the fullest extent you can, you will find your own way of success.

What’s next for you, writing-wise, life-wise, whatever-wise?

Writing-wise, getting a routine! That’s all I want! I just want to be able to write when I want to! *laughs*

You sound exasperated!

I am! Like, I’ve been journaling for a very long time, but I still cannot manage to keep a consistent schedule. You can always say you want another book or an award, but I’m content with the practice of my writing right now, and that’s what I’m going to try and improve upon, just the actual art of it.

Dude, this was such a treat. Thank you.

This was so much fun. I’m really glad to have met you.

DANIEL LIU is an American writer. The author of COMRADE (fifth wheel press, 2022), his work appears in The Adroit Journal and diode. He has received awards from the Pulitzer Center, YoungArts, the Alliance for Young Artists and Writers, Columbia College Chicago, Bennington College, the Adroit Prizes for Poetry and Prose, and others.

And, finally, if you enjoyed my interview with Danny, please tell everyone you know about it!

Stay significant, Otters! I’ll be back later this week with a new Damkeeping.

this is so good lol